Every member of a living system has equal opportunity to change it

The whole system’s principle of “equifinality,” a term coined by the father of systems theory, Ludwig von Bertalanffy, holds that in open systems, for those that have external interactions, a given end state can be reached by many potential means. To lock on to a single pathway, observation or solution can overlook a simpler or better way to reach a goal. The advice then is to reserve judgment and keep an open mind.

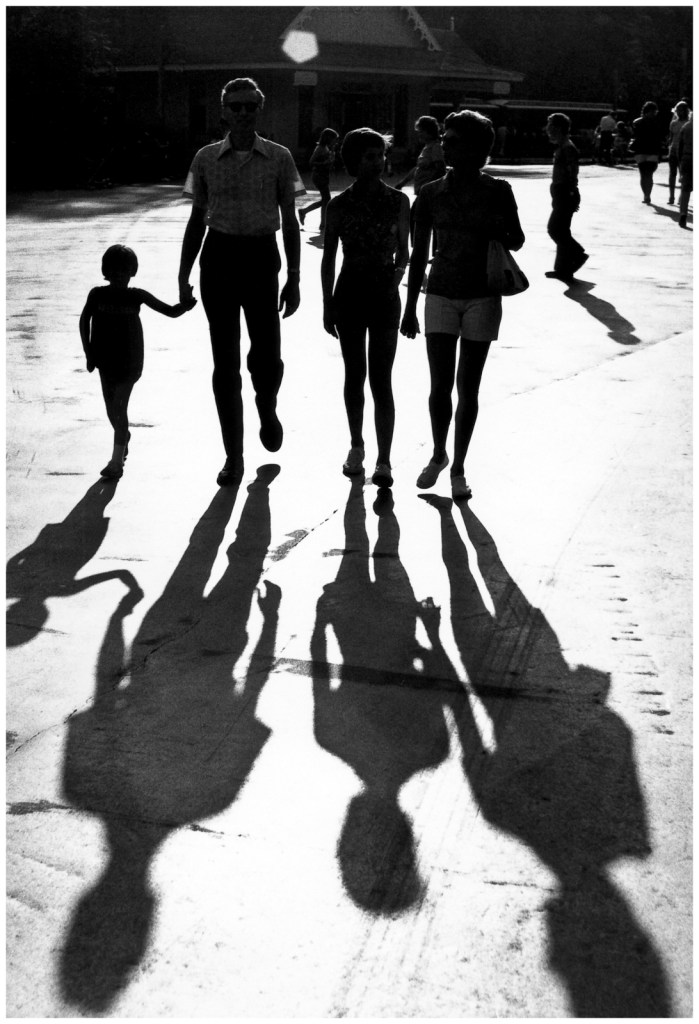

Beyond ideas and perspectives, equifinality has implications for individuals within social systems, suggesting that each member has equal opportunity to affect the outcome of the whole—by paying attention to potential solutions and staying open to alternative pathways to reach a goal, noting that any change will affect the output or outcome. Change any element, person or function, however slightly, and the system will perform differently than it otherwise would. Stated positively, no matter how small, invisible or seemingly insignificant a person’s function within a system, they exert an influence on its performance and outcome.

A rock group is an open system composed of interacting members. As such, it performs differently each time the performers take the stage. Things happen. One musician substitutes for another. A guitar is not properly tuned. The drummer is trying out new sticks. The lead singer is depressed. An amplifier is replaced and now the sound is different. Likewise, corporate cultures change when an employee begins to eat lunch at his desk, when a mother brings her toddler to work, when an executive begins wearing jeans and when employees begin working at home.

It’s why we can’t step into the same river twice. Every millisecond, the water molecules are exchanged; stones move; leaves fall in; the wind and fish contribute to turbulence. An example I cited for my students has to do with film and television production considered as a social system. Change one word in a script, decide not to stop for lunch, swap out a microphone or a light, the outcome is altered. We see it at work in movie remakes and television series. Success in the first movie or episode generates more money, more expensive talent and new writers who have their own ideas about what will succeed in the future. Time and larger budgets bring about changes and suddenly The Good Wife isn’t so “good” anymore, Sherlock’s cases become more complicated and are anything but Elementary and Person of Interest shifts from stories about people to cyber warfare. In other corporations, even churches, a new person at the top affects widespread changes. Understandably, they want to make a difference.

Personal and Social Consequences

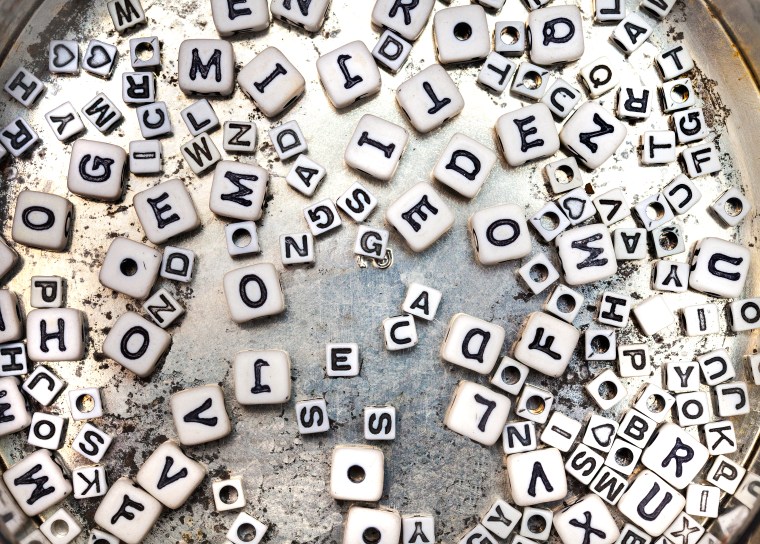

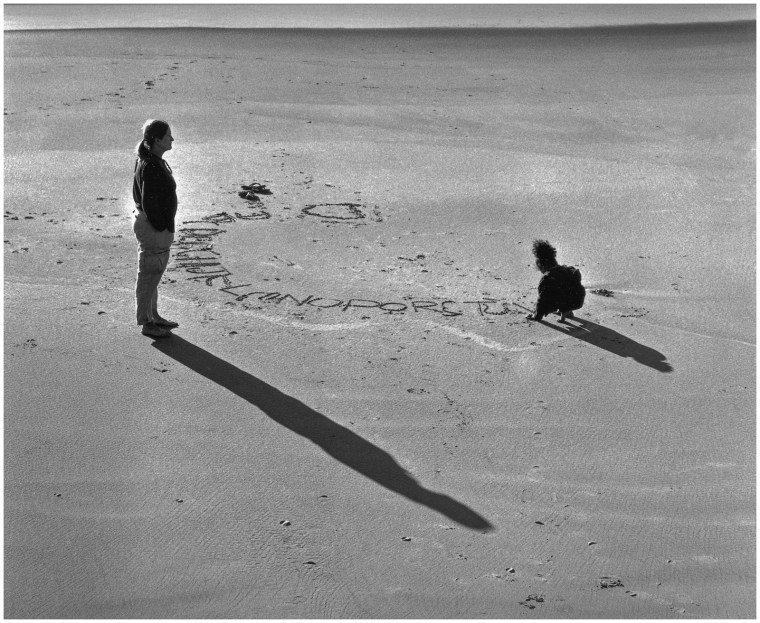

In the above photograph, each lettered tile is a bit of data. Displayed as they are, the whole represents a field of potential, meaning the letters could be put together in a staggering number of ways. Like magnetic letters on a refrigerator door, a child could use them to spell the word “dog.” Another child could use the same three letters to spell the word “god.” The equifinality principle gives us a reason to appreciate that everyday choices and behaviors make a difference, whether intended or not.

Linda’s switch from merely “fresh” to “organic” head lettuce affected changes—in our bodies, for the local supplier, farming systems and health systems, even the economy. Slight, yes. But nonetheless real. And little things add up. Every time we turn on the radio or television or engage in social media, we contribute to the sustainability of the medium and cast a vote for more of its content and upgrading.

Currently, we’re being made aware of the marketers behind the curtain, quantifying every decision we make, modifying their systems; accordingly, there’s big money in monitoring individual choices and behaviors. And the principle can be used to purposefully affect change. For instance, Linda and I are telling certain restaurant cashiers why we prefer paper rather than plastic cups. And in other circumstances we bring our own cloth napkins and saltshakers. These are small things, but in many instance people either learn how they affect the environment or appreciate our choice.

Knowing that my choices and behaviors are affecting change, I can be more aware and deliberate. Do I really want to sustain this activity or business? Do I want to cast a vote for more of this product to be produced in this way? Is this information, service or philosophy in alignment with my values? Does the situation lift me up or inspire me? Do I want to support a company that isn’t socially responsible or ecologically aware?

It occurs to me that this sounds like a lot of self-regulating introspection. Editing this post, I hesitated and observed that the individual words, ideas, and questions I’m expressing are affecting you, and who knows what else. I paused. Do I really want to put this information and these self-regulating questions out there? Indeed, I do, because I’m advocating that we become aware that even our smallest decisions are making a difference—and that difference can affect positive change.

Full disclosure, there are times when I go against the voice of my authentic self, as when I consume more sugar and television than I know I should. Sometimes we just want what we want—and we accept the consequences. On balance, however, I find comfort in the act of making “a good faith effort” as often as possible.

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.

Margaret Mead, Anthropologist

I welcome your feedback at <smithdl@fuse.net>

My portfolio site: DavidLSmithPhotography.com

My photo books: <www.blurb.com/search/site_search> Enter “David L. Smith” and “Bookstore” in “Search.”