Our collective consciousness created it

Left to right: Sven?, Fran Macy, Donald Keys (Moderator), Gehard Elston, Bill Porter

In June 1983, under the auspices of the World Good News Network (WGNN), I led a team to Toronto, Canada to video document a week-long event entitled, “The Congress of the Planetary Initiative for the World We Choose.” 470 people—delegates, scholars, scientists, artists, psychologists and concerned citizens—met to raise awareness that the future is in our hands, and that the anxieties and challenges of the global mega crisis could be surmounted creatively and constructively through personal involvement. Years before a collaborative network called “Planetary Citizens” had created a global process of dialogue at the grassroots level on topics relating to planetary welfare. Besides raising awareness, the Congress built hope for the future by demonstrating that everyone can become a co-creator of a more desirable world and humane future. At the end of the event a consensus statement was presented, emphasizing specific steps and recommendations for achievement. (The 2-video summary report is available here. Part 1 – 5:50 / Part II- 13:51)

One of the presenters at the Congress was Ram Dass, an American spiritual teacher, guru of modern yoga, psychologist and writer. His seminal, best-selling 1971 book Be Here Now, helped popularize Eastern spirituality and yoga in the West. In an interview with him I asked if, in fact, we’ll get the world we choose. Without taking a beat he replied, “We are getting the world that we choose. This is it! This is it! You look around, this is the one we’ve created… the fear of the bomb and ecology and population explosions and all of these things are part of the conditions that you, as a soul, created for this incarnation in order to awaken out of the illusion of separateness. And it’s all going fine… as a human being you are afraid of death, and as a divine being you’re not afraid of death, and you’ve got to embrace that paradox. It’s from that place that you can look at the situation and see it as a learning experience. Otherwise, it’s just too scary.” (Look for the last video on his page. It’s just1:41)

Process

A society’s collective consciousness creates its reality in many ways. The processes are well documented across the fields of sociology, philosophy, systems theory, neuroscience and contemplative traditions. “A change in consciousness is the prerequisite for a change in the world.” — Ervin Laszlo, philosopher of science and systems theorist.

Perception: We create by what we see, what is ignored and how events are interpreted. Examples include, seeing nature as a “resource” rather than a sustainer of life or “sacred presence,” viewing homelessness as a moral failure on the part of individual living on the street instead of systemic breakdown and viewing economic growth as the key to well-being and happiness. “We see the world, not as it is, but as we are.” — Anaïs Nin, French novelist.

Meaning-Making: Social systems create meaning through storytelling, myths, metaphors and shared language. For instance, we’ve largely defined “progress” as technological expansion, “success” as wealth, accumulation and status and “security” as domination or control.

Value Prioritization: Mass consciousness establishes implicit hierarchies of value—profit over ecological integrity, new versus old, appearance over substance, entertainment over work, and individual achievement over social benefit.

Norms: We tend to fall in line according to prevailing behaviors—endless consumption, overwork as a badge of honor, romance portrayed as love, chronic anxiety as a fact of life, the purpose of education is to get a good job; the purpose of work is to earn a living. Everyday people can’t change the system, and “freedom” gives me the right to do what I want.

Institutional Structures: Many educational systems are designed to support industrial productivity. Healthcare is structured around symptoms rather than whole-person assessments. Corporate heads are not held responsible for their faulty decisions. Mass media are driven to maximize attention and election rules favor the wealthy. “A nation’s culture resides in the hearts and in the soul of its people.” — Mahatma Gandhi

Identity: Whether or not we agree with the labels, our identity as individuals and nation are prescribed by the collective consciousness, and are largely reinforced by leaders who categorize people: “patriot,” “Immigrant,” “Republican, ” “Liberal,” “Jew” “Catholic” “Guru,” “Atheist,” “Executive,” “Housewife,” “Criminal”…

Beliefs: For instance, the idea that the ecological collapse is unavoidable, that climate change isn’t real, inequalities are simply “nature’s way, “a rising tide lifts all boats,” “winning is everything,” and “God is on our side.”

Spiritual Orientation: Every society, explicitly or not, addresses the questions of life’s meaning and mysteries. The collective religious/spiritual consciousness shapes morality, ethics, personal and national purpose. It determines whether life is seen as sacred or accidental and influences how suffering and death are understood. “The fate of humanity depends on the moral strength of the individual.” — Albert Einstein

The Institutions We Have Chosen

While there are many social institutions that contribute to the collective consciousness, there are two in the United States that stand out as examples of choice, because they’re interrelated and interdependent—the mass media and presidential elections. We collectively created them as they are, and we’re sustaining them by the choices we make—or allow. A quote from politician-philosopher Edmund Burke’s comes to mind regarding how everyday people create through passive acceptance of the status quo. “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” I’m not saying these creations are bad or evil, just that doing nothing about aspects of them we don’t approve of is a choice. The current state of the media and elections are just an indication of where we are on the evolutionary trajectory of experimental civilizations.

The Media

Attention = political capital. The mass media—television, radio and now social media in particular—drive our social and political realities by calling us to the electric “campfire.” By presenting people who are important, entertaining, unusual or interesting, and outputting similarly structured events, the status quo and those on “stage”—celebrities, politicians and “friends” are legitimized. So, in a very direct way, by continuously focusing our attention on the campfire and the stories told there, we’ve created our world. As long as we give anything or anyone our attention, we’re sustaining it.

What are those “stories” telling us? After watching a week’s worth of television, an alien from an advanced civilization would conclude that, on the whole, intelligent life on Earth is in its pre-adolescent phase of development—quick to anger, ignorant of who they are, self-absorbed, seeking greater independence, competitive, fascinated with body functions, regards violence as a quick way to solve problems… Also, by framing and dramatizing differences of all kinds as a competition across genres—which maximizes attention—the electronic media fan the flames of division.

While this may sound like criticism on my part, that’s not my intention. I believe humanity is undergoing the necessary evolutionary means by which we situate ourselves in the cosmos, learning right relationship with each other and the planet, choosing what works and rejecting what doesn’t, gaining an appreciation for citizen power and the methods by which perceptions, beliefs and values create our reality. It seems to me, this is the next step toward understanding who we are, why we’re here and what we can become when united in love. The evolution of consciousness advances at a glacial pace, but it may be comforting to know the seeds of transformation already are blossoming within the crisis. (See my blog on “The Story of Emergents.“)

Presidential Elections

In the United States, the presidential elections are not “rigged,” they’re managed—by a Supreme Court decision that allows wealthy individuals to contribute millions of dollars to various political entities, thereby boosting big-donor influence and enabling the rise of Super PACs, by television airtime focusing on candidates with the most money to spend on advertising and attention-getting displays of personality and by candidates reverting to “political-speak,” using memorable and emotional language, speaking in sound bites and generalities lacking in context and evidence to support their views.

As with television creators, politicians maximize attention in order to “massify” an audience. To be successful then, these systems, which “we the people” created and sustain, must appeal to the lowest common denominator. Esteemed television news anchor Walter Cronkite closed his newscast with the comment, “That’s the way it is…” Really? Was that the whole picture? Rude, crude, violent, perverted and cheating? Is that what it means to be “human.”

Lacking substantive information, many voters turn to substitutes for trust, qualities of character and truth in choosing a President. They ask: Does the candidate feel “real.” Does he say what he thinks? Is she tough enough? Is he my kind of guy? According to Lilliana Mason, professor of political science, “People vote their identities more than their interests.” Does the candidate validate my anger? Is she willing to break the rules? Is he a straight-talker, framing issues in black and white; for us or against us? Will she attack the established order and bureaucrats?

After writing this last paragraph I asked an AI program to “prioritize the personal attributes, consciousness and worldview of a person most likely to serve effectively as President of the United States—considering national security, the economy and foreign relations.” The response was way too long, but it produced this insightful synthesis—

The most effective President of the United States is not defined by ideology or charisma, but by emotional regulation under threat, cognitive complexity, epistemic humility, and a systems-level worldview. Such a leader operates beyond tribal identity, understands power as relational rather than coercive, and governs with time-depth awareness—balancing national security, economic vitality, and foreign relations within an interconnected global system… In an age of complexity, the greatest danger is not weak leadership—but simplistic leadership.

So, What Can We Do?

Within and beyond ourselves, what can we do to affect the collective consciousness? In a speech at the Planetary Initiative Congress, futurist Barbara Marx Hubbard described the process of “Navigating Evolutionary Change” (videos). She encouraged the attendees to join with likeminded others to affect a graceful rather than violent shift by contributing to the formation of a “critical mass” of positive, socially responsible consciousness. Her point, relative to this topic, was that although social realities are shaped one mind at a time, they are never shaped by isolated minds. What it takes are minds connected in resonance, singing the same song over time. It’s why, decades later, the viewpoints and energies expressed at the Congress gave birth to hundreds of organizations worldwide focused on coherence, forming a critical mass engaged in personal growth and spiritual development, with initiatives in peace and planetary stewardship.

On The Inside

Meditate and contemplate. I can assess how I’m seeing and what I’m doing. What am I bringing to this moment? Is it consistent with my purpose in life? Is this a good use of my time? Choose from my higher self. Engage soul before hands and feet. What are the consequences of this act—for me, those close to me, society and the world. Is this a reality I want to support? What am I getting out of this? How does this make me feel? Pause and think before acting. Hold beliefs lightly. Replace “being right” with “seeing more clearly.”

As human beings, our greatness lies not so much in being able to remake the world, as in being able to remake ourselves.

Mahatma Gandhi, Indian lawyer, political ethicist, spiritual teacher

On The Outside

Consciousness becomes culture through participation, speaking, listening and showing up. And as Barbara Marx Hubbard urged, engaging with like minded others. What else can I do? I can speak with everyone in ways that preserve relationship, reduce exposure to outrageous and disturbing media, support journalism that informs rather than inflames and practice deliberate consumption of information. “We become what we pay attention to.” (William James, Philosopher, psychologist). I can invest my energy in local organizations and institutions, support cooperative and restorative initiatives, commit to living authentically, accept gracefully whatever life (soul) brings, share stories of success and healing, seek inspiration and awe, engage in creative activity and walk in nature.

Every thought, word and deed, positive and negative, is at some level a contribution to the world. Listening, acting and responding are never just personal. How we are in the world, our choices and expressions, have political, cultural, spiritual and ecological consequences. A different reality is built by a critical mass choosing to think and perceive differently—and act accordingly. Ram Dass rightly said, “This is it!” We’re getting the world we chose by being born into this place and time and falling in line with the prevailing “climate”—consciousness and behaviors. Fundamentally, climate change is waking us up to our role as world creators. Knowing that, like it or not we are contributing, we can shift our thinking and make choices that are more authentic to our both our inner and outer reasons for being here.

Wanderer, there is no path. You lay a path in walking.

Machado, Spanish poet

__________________________________________________-

My other sites:

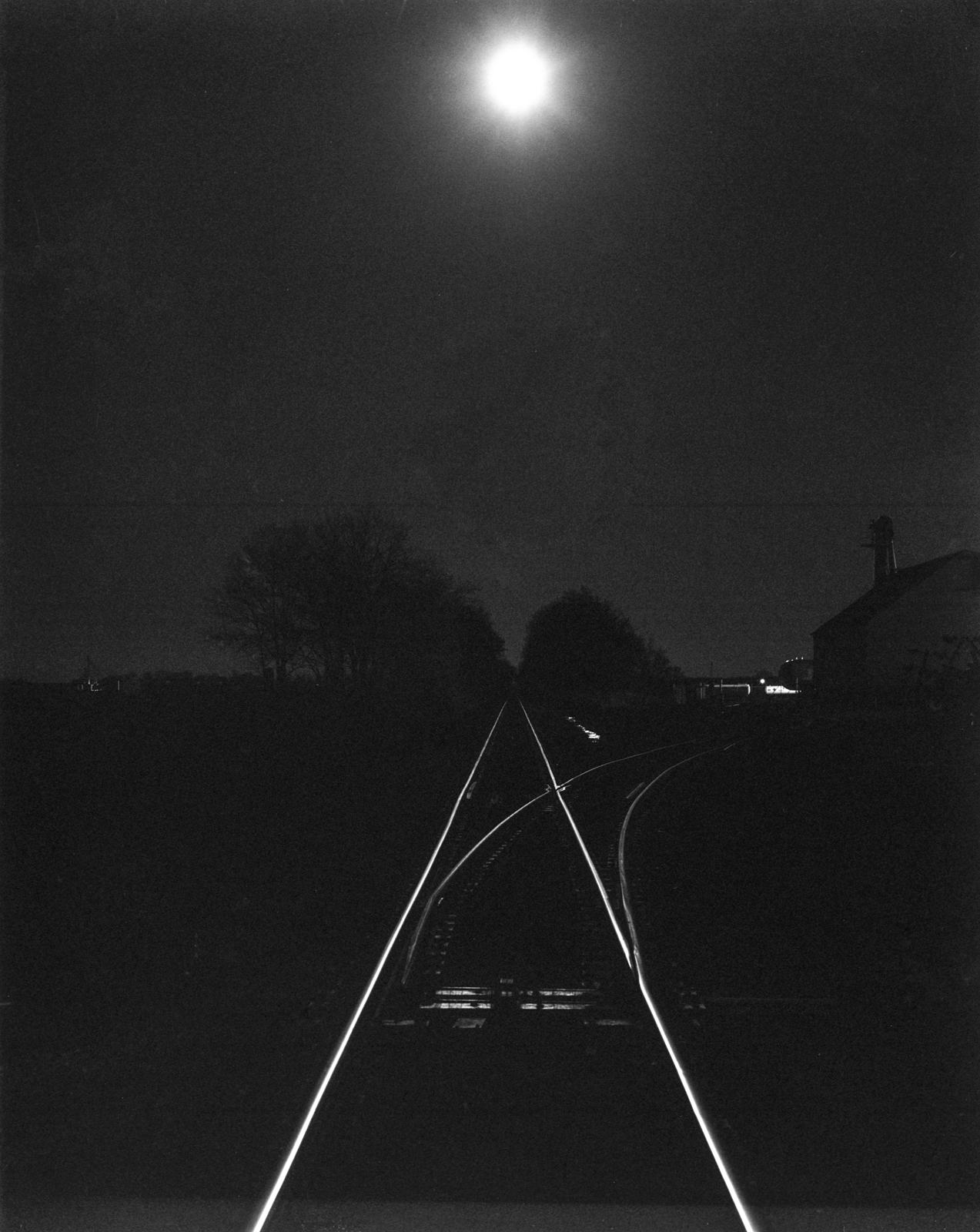

David L. Smith Photography Portfolio.com

Ancient Maya Cultural Traits.com: Weekly blog featuring the traits that made this civilization unique

Spiritual Visionaries.com: Access to 81 free videos on YouTube featuring thought leaders and events of the 1980s.