Chapter 3: Light and Lighting

Regarding the mystery that light is, physicist Arthur M. Young wrote in The Reflexive Universe: Evolution Of Consciousness, “Light, itself without mass, can create protons and electrons which have mass. Light has no charge, yet the particles it creates do. Since light is without mass, it is nonphysical, of a different nature than physical particles. In fact, for the photon, a pulse of light, time does not exist. Clocks stop at the speed of light. Thus mass and hence energy, as well as time, are born from the photon, from light, which is, therefore, the first kingdom, the first stage of the process that engenders the universe.” Because light is central to image making, those working with it pay attention to its characteristics, at times selecting and altering different sources and light shaping instruments according to their expressive need, intention or communication objective.

SUNLIGHT

Sunlight is not just illumination—it’s a dynamic, emotional, and symbolic element that can shape the entire mood and meaning of an image.

Direction

Hard: Cloudless mid-day sun creates high contrast with deep shadows that have sharp edges.

Soft: Clouds, fog and mist spread the light to create blurred shadows, if any.

Front light: Tends to flatten forms but can enhance color saturation.

Side light: Enhances textures, form and depth.

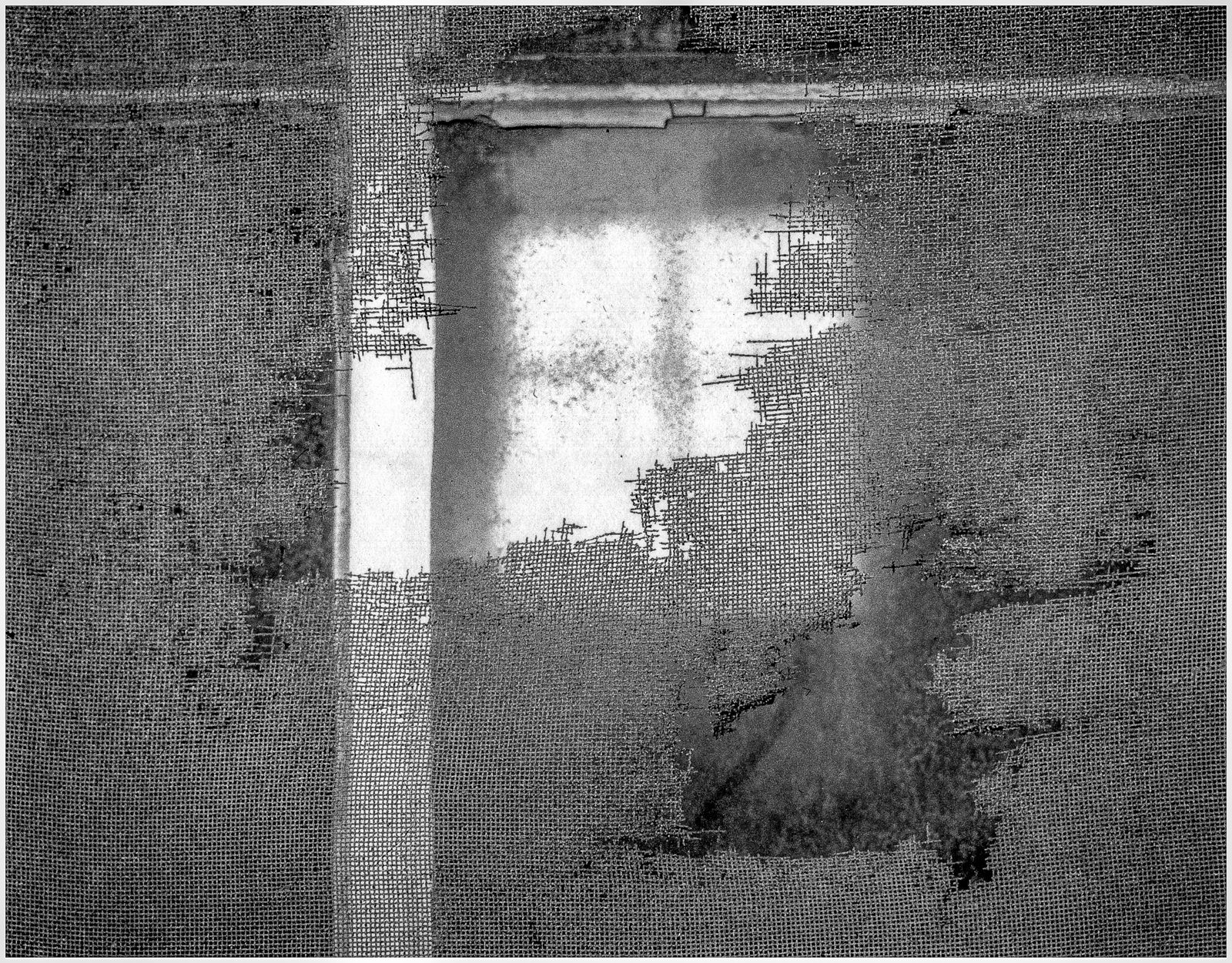

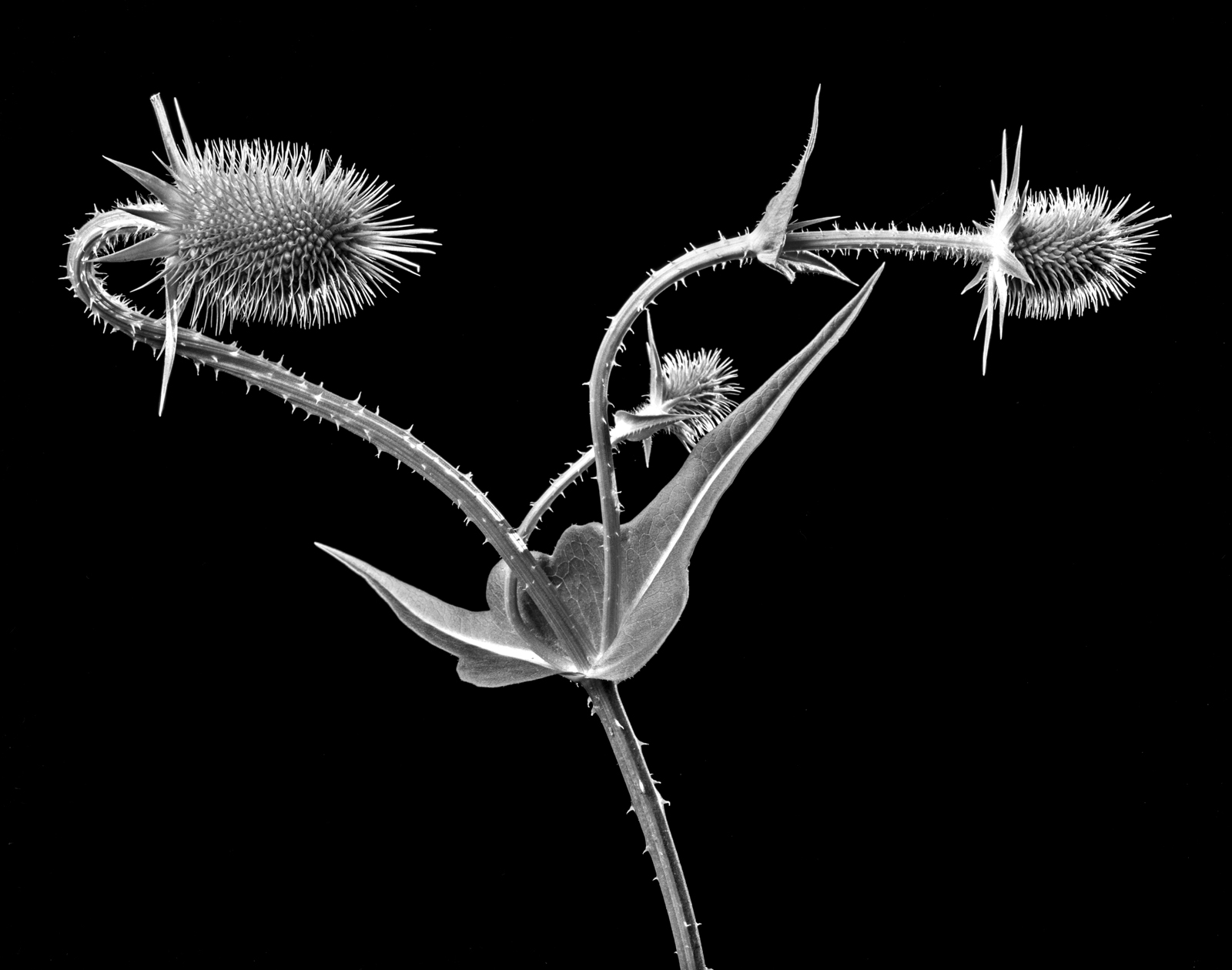

Back light: Silhouettes and halos; enhances patterns in translucent material (leaves, fabric).

Top light: Mid-day sun can be harsh, stark.

Color

Magic Hour: Just after sunrise and before sunset; warm, amber glow, long shadows.

Blue: Before sunrise and after sunset; cool, moody tones; calm and quiet.

Mid-Day: Neutral; emphasis on information rather than expression.

Symbolism

Sunlight can evoke a perspective on the immensity of the earth and cosmos, and signal enlightenment, transcendence, revelation or the divine.

ARTIFICIAL LIGHT

Film and digital image makers rely on variety of light sources and light shaping instruments. A primary consideration is the relative sharpness of shadows, ranging from highly “specular” to very “diffused.”

These bulbs were lit from the side to cast shadows. The source was a clear 200W bulb, identical to the one shown at top left. Being a specular source, the edges of the shadows are sharp.

- Top left: Clear, 200 watt incandescent bulb with 2 1/2″ filament (specular)

- Top middle: Frosted LED bulb (very diffused)

- Top right: 200W frosted incandescent bulb (diffused)

- Middle: 250W clear quartz halogen bulb with 2 1/2″ filament (bright ‘ very specular)

- Bottom left: 500W frosted quarts halogen tube with 4″ filament (very bright and specular)

- Bottom right: Clear 250W quarts halogen bulb with 1/2″ filament (extremely bright). Of those shown this bulb yields the highest degree of specularity because its filament is so tiny.

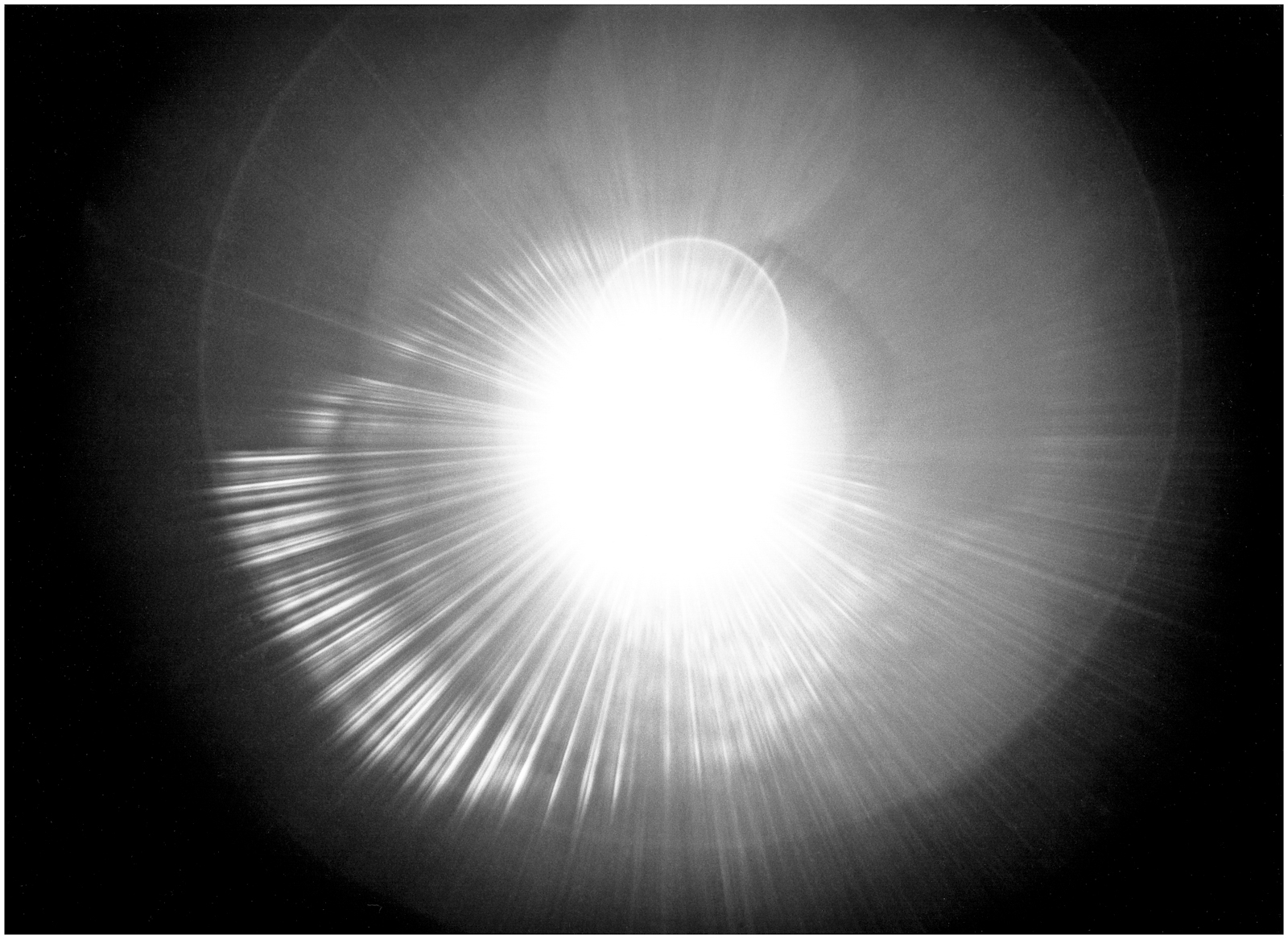

SPECULAR LIGHT

A light source is considered “specular” when it’s not modified by any kind of diffusion material. The tinier the filament, the greater the degree of specularity. The telltale sign of these bulbs is the sharpness of the shadow they cast. The sharper the edges, the greater the specularity. Highly specular lights are commonly used in jewelry store ceilings, windows and counter displays to create sparkling highlights in the facets of gemstones and metals. In this light, their slightest movement makes them sparkle.

Professionally, quartz (tungsten-halogen) bulbs have been the standard for many years. They have excellent color consistency and they cost less than LEDs, which emit very little heat, are safer, use less energy, last longer, can vary in color and are lighter than quartz to transport. But unlike quartz bulbs, which can stand alone, LEDs require a special fixture or focusing device to make them emit a specular beam. And that increases the cost.

CAUTION: Never touch a quartz bulb with your fingers. When the bulb lights, the oil from fingerprints instantly melts and the bulb explodes. Early in my career as a cinematographer I witnessed this once. It sounded like a shotgun going off. No one was hurt, but shards of molten crystal burned for several minutes into the wood desk they landed on. In the industry, as a safety precaution, whenever someone is about to turn on a quartz light where people are close by, the practice is to first turn the light away and call out “comin’ up!” In nearly three decades of working with students in a studio setting where all the lights were fitted with quartz bulbs, not once had there been an accident. Quartz bulbs are excellent, but they have to be handled with care.

Creative Application

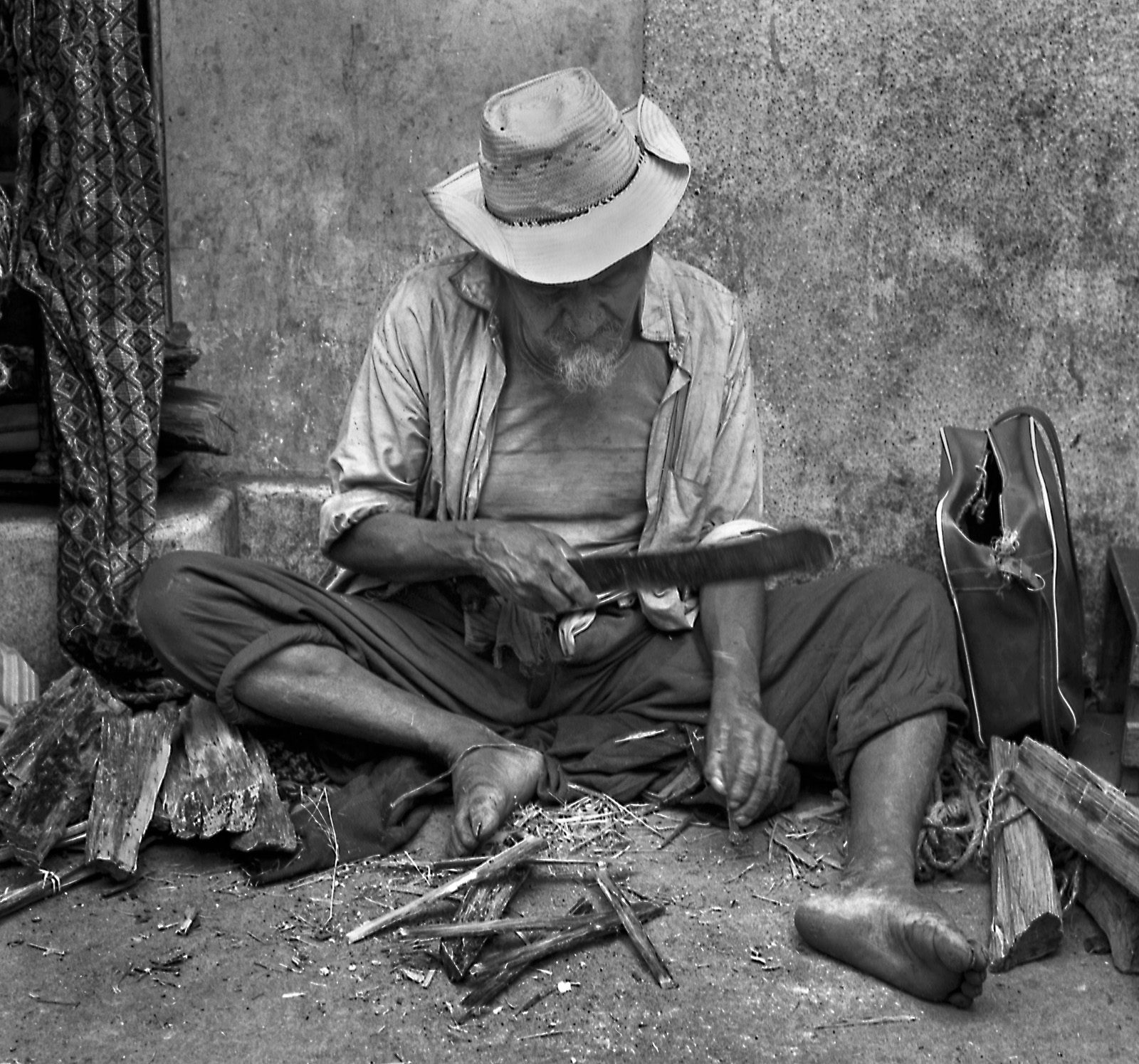

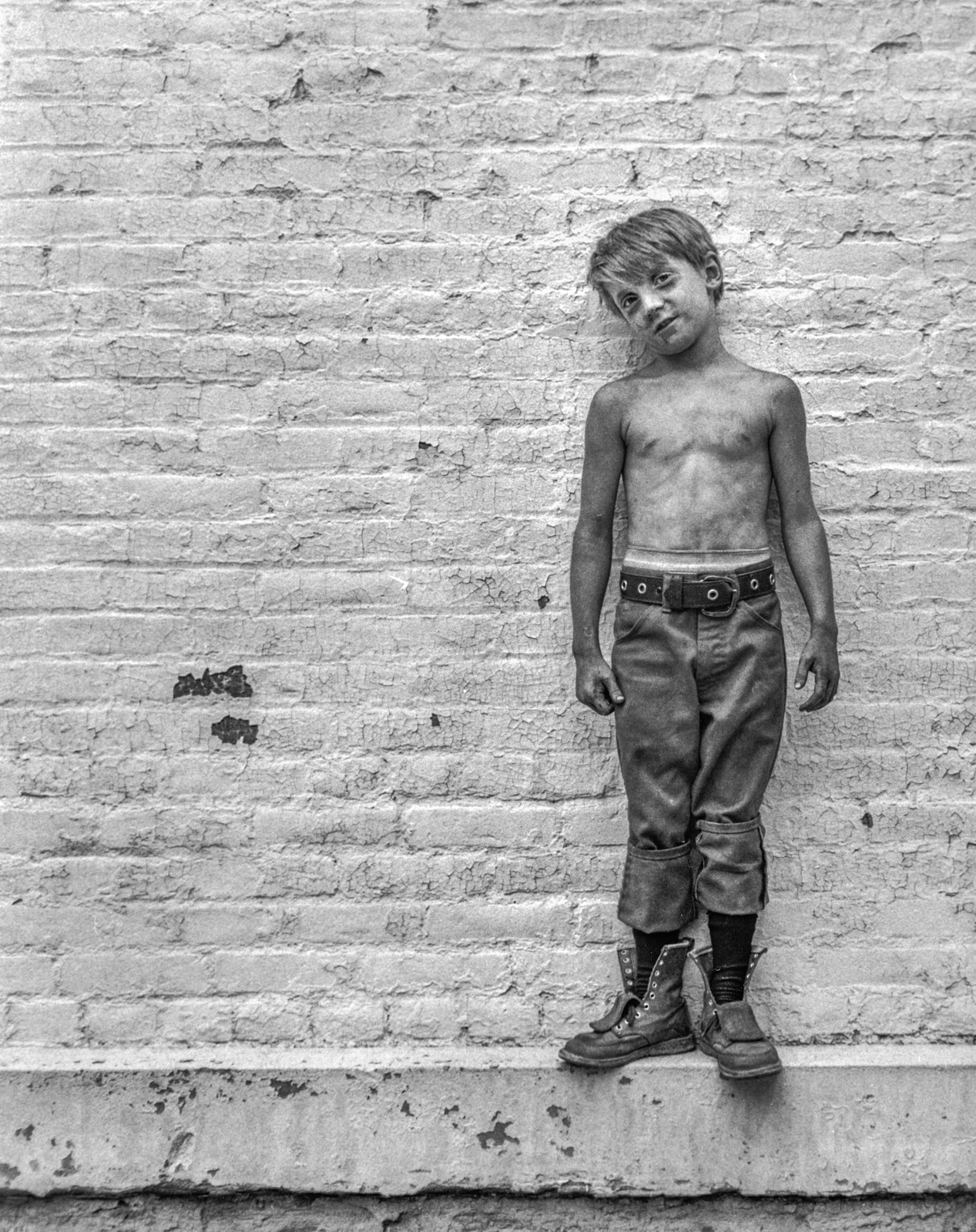

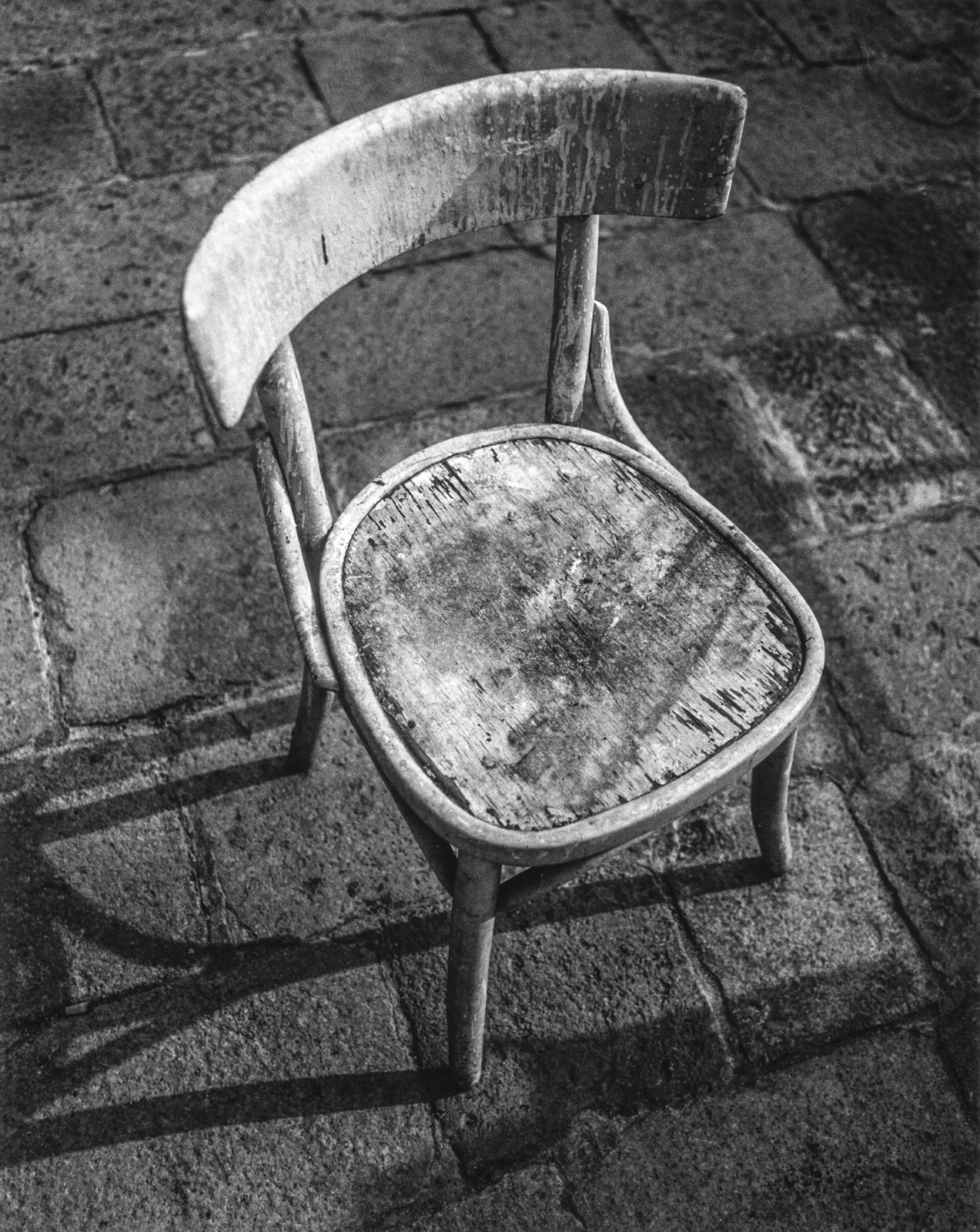

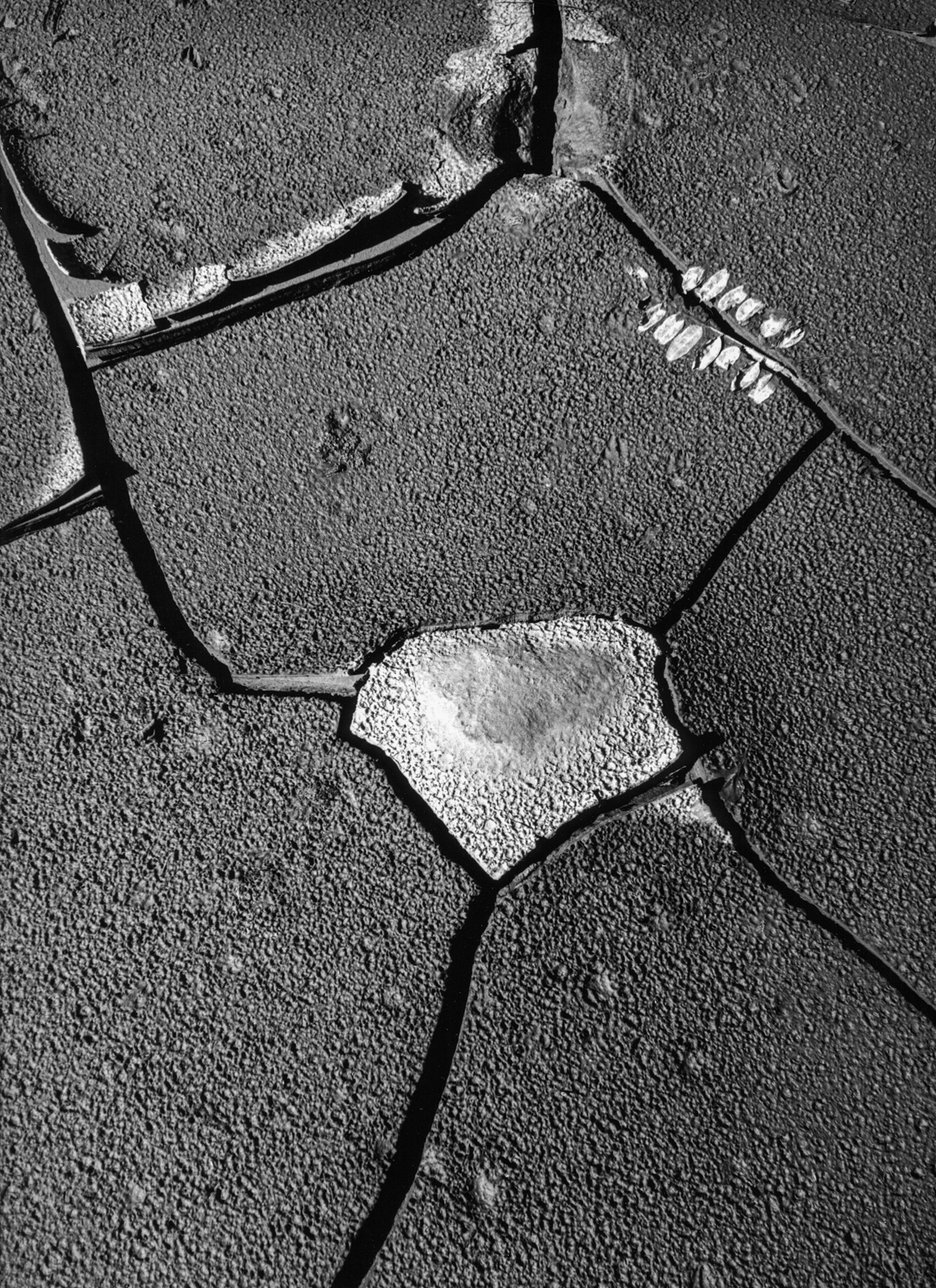

Because specular lights produce hard-edged shadows and crisp highlight, they enhance detail and texture, especially when directed from the side; the more to the side, the longer the shadows. This makes them ideal for emphasizing rugged skin and beards, fabrics and weathered surfaces such a driftwood and peeling paint. In portraiture, it’s common to use a specular light as a “kicker” or “backlight” to create a sense of depth by separating the subject from the background. It also contributes to the modeling of form in architecture, fashion and product photography. Emotionally, specularity shouts; it’s not subtle.

Specularity is employed when the expression or communication objective is to create a sense of “brightness” or “crispness,”—and increase the sensibility of texture. Unlike most of the other aesthetic dimensions that express either emotion or information, specular lighting accomplishes both at the same time.

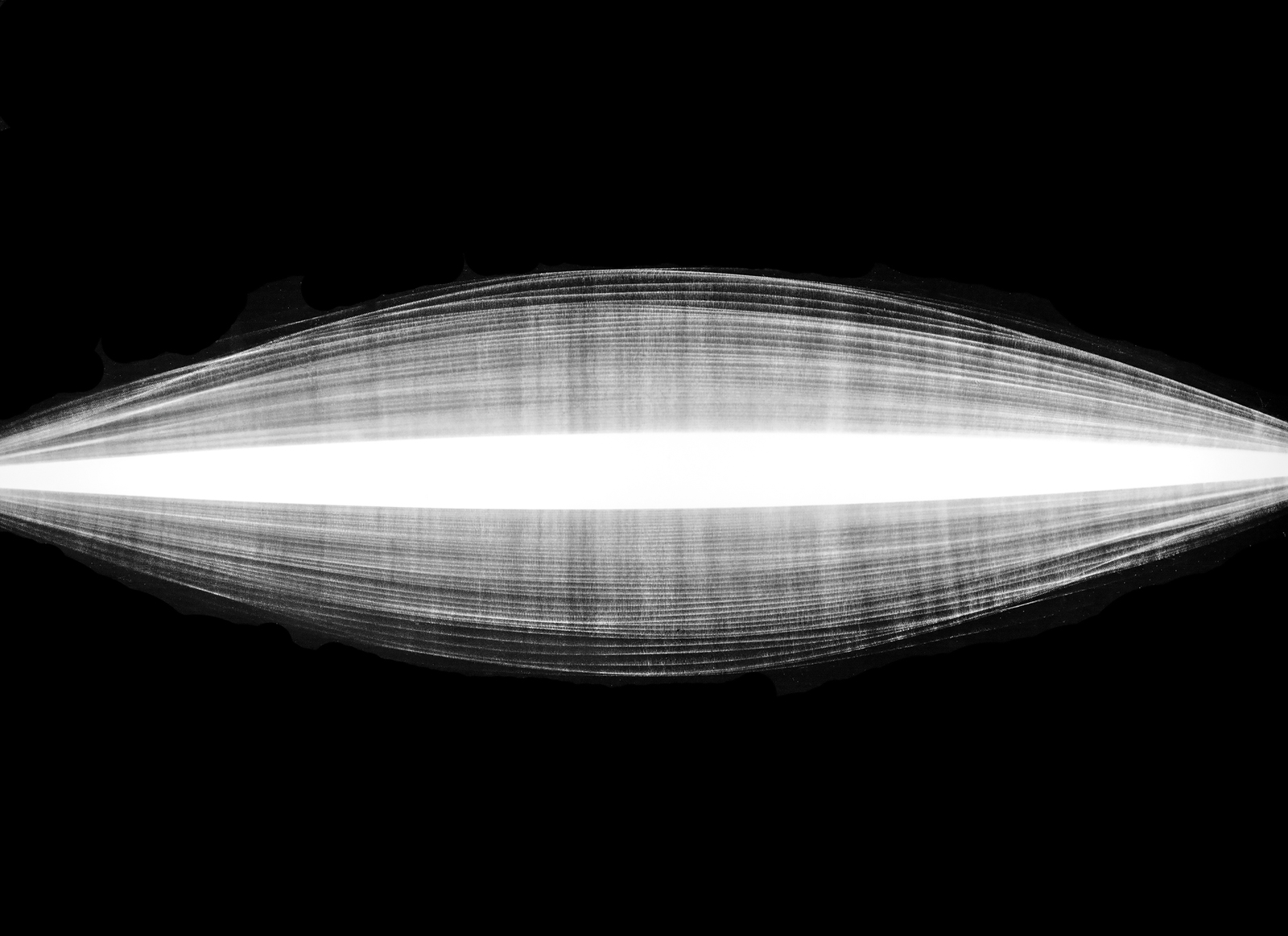

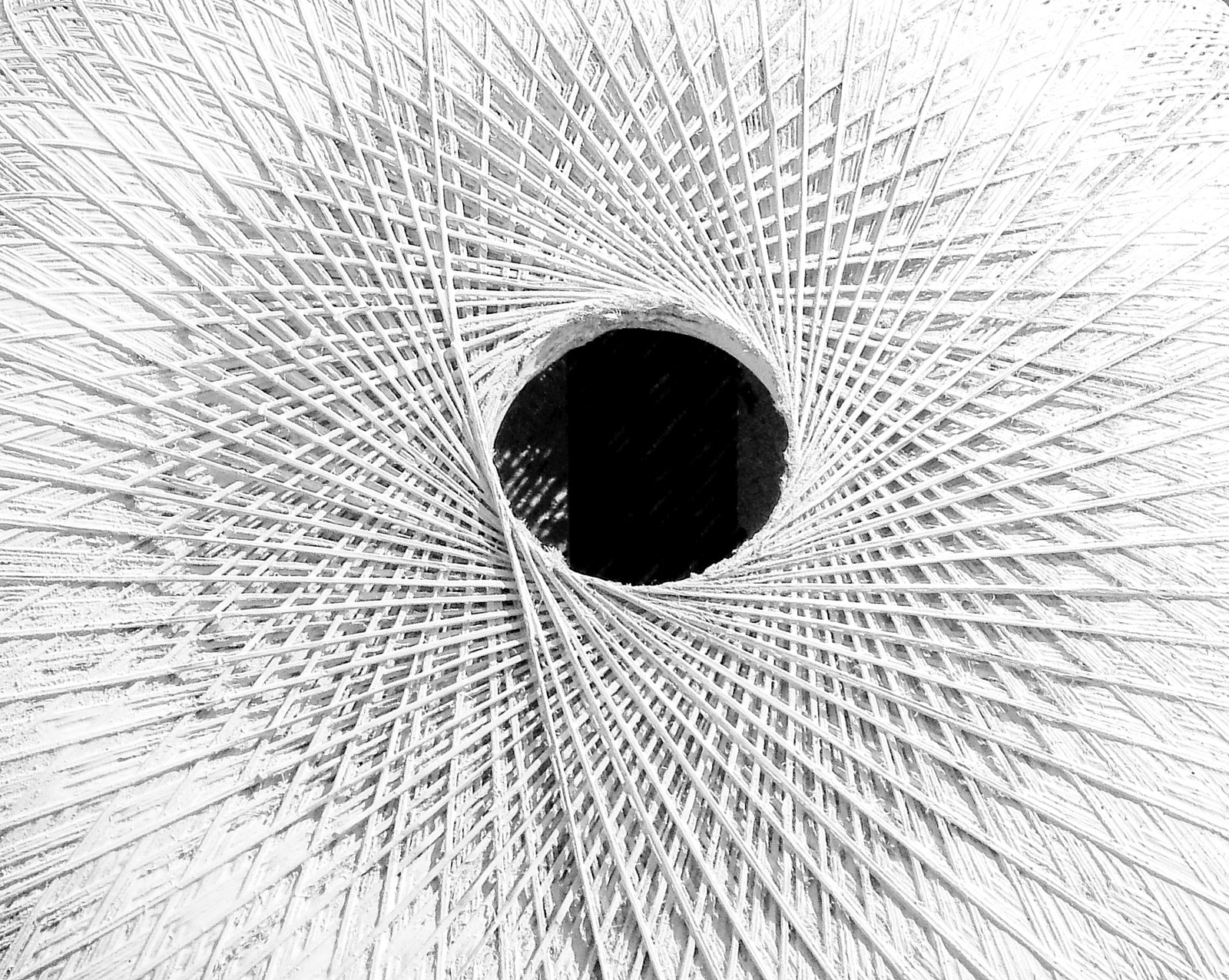

DIFFUSED LIGHT

The more diffused the light, the softer the look. It’s desirable in both expressive and commercial situations, especially in the realms of glamour and fashion. The softening effect is heightened by having a diffused source positioned above the subject, whether people or objects. As seen here, however, with the light more to the side, the graded shadow on the opposite side of the rounded form is spread longer. The light on this bowl grades downward from the rim. Diffuse lighting, whether indoors or out, is warranted when the expressive intent or communication objective is to emphasize the emotional sensibility of smoothness, roundedness or depth. It’s not so good at providing information.

Compare this image with the one above. It’s the same photo as the one displaying specular light bulbs, only this was lit with a diffused source. Notice how the edges of the shadows are softened, blurred and graded. When there is anything behind or in front of a filament, be it metal or plastic, the light becomes softer with spread out shadows. The denser the diffusion medium—clouds, fog, diffusers, colored gels—the fuzzier the shadows. Any kind of coating on a bulb or tube diffuses the light. Fluorescent tubes are almost always coated, commonly used in large areas such as department stores and offices to soften the look of fabrics—and they’re easier on the eyes. Upscale restaurants use diffuse and dimmed lighting to create a soft ambiance. The electric candles on tables usually have small lampshades to diffuse the otherwise specular bulbs.

Creative Application

Diffuse lighting is subtle and soft, revealing without overpowering. It wraps around subjects with graded shadows and reduced contrast, creating a more contemplative sensibility. It’s ideal when the intent is to create a feeling of flow, softness or subtle moods. Considering the unsharp shadow edges, highlights and shadows are closer in tone. Whereas specular lighting shouts, diffuse lighting whispers. For these reasons, it excels in expressing emotions and conveying beauty.

Tools

Photographed with permission at Dodd Camera, Cincinnati, Ohio

The industry that serves professional image makers has developed an enormous verity of lights and light-shaping instruments designed to create various sizes and levels of diffusion. These include softboxes, diffusion panels, umbrellas and materials such as translucent sheets of plastic, frosted plexiglass and wire frames that attach to lights. Ordinary white foam core also serves as an inexpensive reflector. Another way to create diffuse lighting is to bounce lights off a white wall or ceiling.

Painting with Light

Kenwood Baptist Church, Cincinnati, Ohio

At night, I set the camera on a tripod with the aperture at f16 and the shutter set for a time exposure. After opening the shutter I walked around this property setting off bursts from an electronic flash. I made 15-20 flashes in the space of five minutes, constantly moving with my back to the camera and the flash unit in front of me. Finally, I laid on the ground and pointed the gun upward to the tree. The huge stained glass window was the only thing that was actually lit. I hadn’t expected the tree limbs to be blurred, but I liked that it gave the image a sort of haunting sensibility.

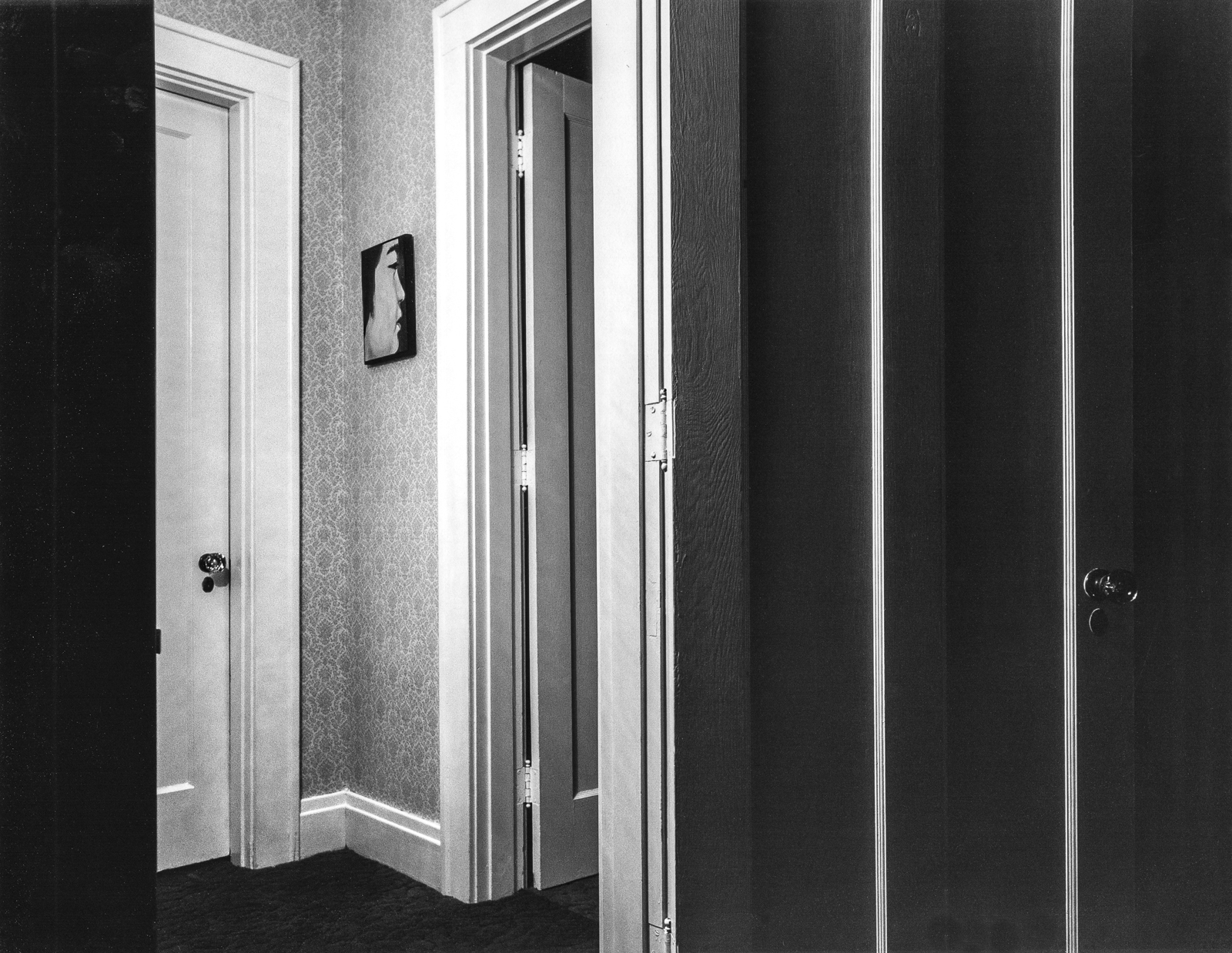

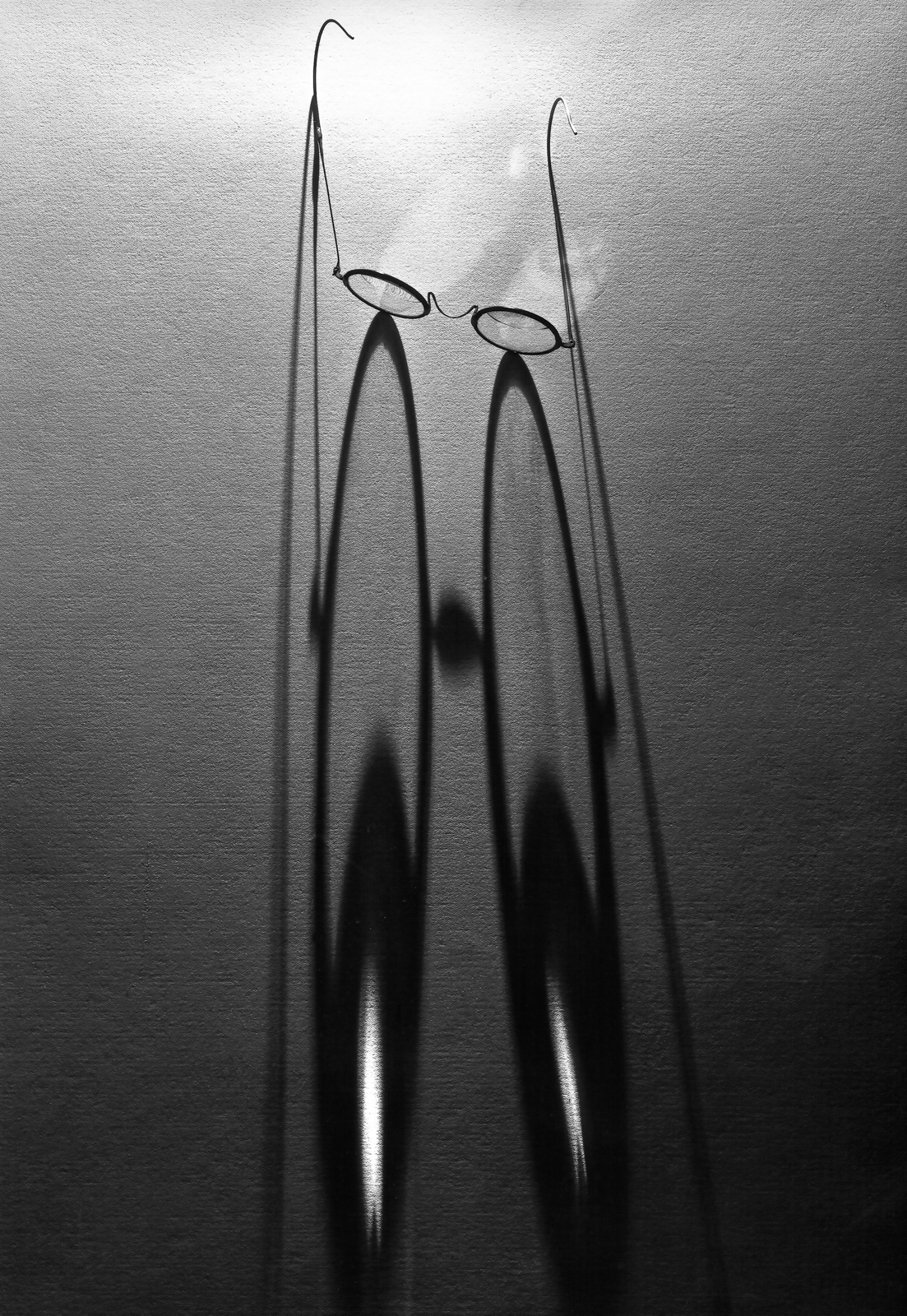

Light as Subject

There’s a quality of light that plays a prominent role in defining form, not just revealing it. Beyond allowing a subject to simply be identified within a frame, it touches the aesthetic nerve, evoking an appreciation of the essence or spirit within or beyond the form. Whether in color or black and white, these images are predominantly black allowing the light to take center stage.

REFLECTION

“Light” is a common metaphor for awareness. We picture a lightbulb and say we had a “bright idea.” And when Indian sages attain realization, they speak of it as “illumination.” Basically, the metaphor expresses a new or heightened state of awareness or consciousness. Considering the recommendation to pay attention to what the light is doing in order to create an image; questions comes to mind regarding the place of light in everyday experiences—our frames of reference.

What are my thoughts doing? Along what lines are they being directed? Where am I “pointing” my attention (the camera equivalent)? Am I creating the reality I want—by purposefully managing my attention? Or am I allowing it to be directed by outside influences? It’s the difference between directing and reacting, living authentically, consistent with one’s purpose, or operating on auto-drive.

This prompts another line of questioning: What images am I creating—and what am I doing as a result of those images? What are the consequences of what I think about most? It’s good to know because whatever we attend to we make more of. There’s no right or wrong, better or worse here. Whatever is consistently on my mind and paying attention is what I’m bringing into my life and contributing to the world.

Increased awareness of a light source, its qualities and functions in our lived spaces as well as in photographic image making, deepens our appreciation for the capacity of sight. Had evolution not provided the combination of eyes to collect certain photon frequencies and brains to interpret them, we would only be feeling the radiation that comes from the sun—and every other source.

Light created the eye as an organ with which to appreciate itself.

Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Poet, statesman

Light is energy and it’s also information, content, form, and structure. It’s the potential of everything.

David Bohm, Theoretical physicist

______________________________________________

My other sites:

Substack: Poetry and insights relating to creation and Creator

David L. Smith Photography Portfolio.com

Ancient Maya Cultural Traits.com: Weekly blog featuring the traits that made this civilization unique