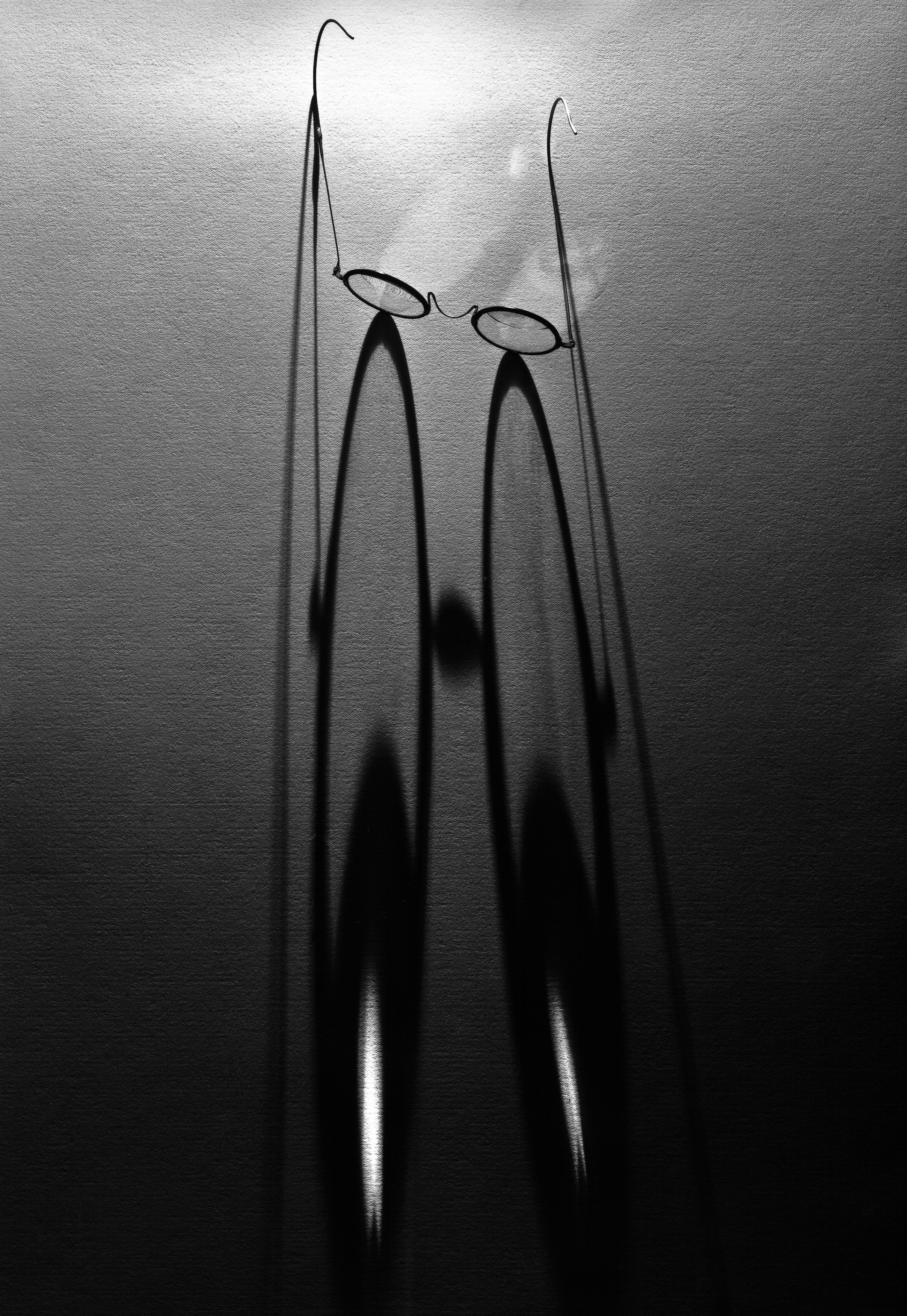

Do you see the beautiful woman bathing at the foot of a waterfall? This isn’t a trick. It’s there. Do you see the elephant? There’s also the Empire State Building, a giant anaconda, the art collection at the Louvrè, my entire photographic collection and that of the Library of Congress. While it’s not a trick, it’s a perceptual challenge because they exist within the frame as potential. In fact, what the interior of this frame carries is potentially a depository of all the visual images ever produced in any form—drawings, paintings, X-rays, photographs, television programs, movies. They’re all there. So also, potentially, are the images that have never been seen, including those not yet imagined or produced. Like outer space which appears to be empty, the content of this frame is not. As with the atom, it’s full of invisible, vibrating fields and forces.

As a blog intended to model how photographs can be used as vehicles for contemplation, this edition is intended as an appreciation of the minds of scholars and researchers who are investigating the “unification” or “nondual” paradigm that’s gaining traction in the sciences. As I consider the areas that peak my sense of wonder and appreciation, I’ll let the professionals speak for themselves.

If you keep zooming in on the image above you’ll eventually see pixels. Each one is a hologram of the whole, pure potential individuated. It can be turned on or off, emit bright light, no light at all or the inconceivable combination of luminance values and colors in between. When a cluster of pixels are black, as above, or a blank television, computer, smart phone or movie screen, they are in the “ground state” of pure potential. Whether real or imagined, an infinite number and variety of images can be projected onto them. Okay, so what’s the big deal?

It’s that this simple insight is changing the way scientists are regarding the universe and the nature of Reality. It’s going to affect everyone and everything dramatically. It already has. The proliferation of electronic technologies in the last half-century was made possible by the conscious application of quantum mechanics, the knowledge of which has, in part, led to this shift in understanding. Up until recently the wildly held assumption among scientists has been that matter is fundamental to the universe and that eons of evolutionary process has resulted in a complex brain that produces consciousness. Without a brain there’s no thought. But that turns out to not be true.

Thousands of well-conducted experiments and case studies insist there is an aspect of consciousness that is not physiologically based, and is not limited by spacetime. More than that they propose consciousness itself is the foundation of all that is. Journals in fields as disparate as physics, biology, and medicine published papers of this research. There are so many that each discipline has its own literature. Everything we talk about, everything we regard as existing, postulates consciousness. We must assume behind this force the existence of a conscious and intelligent mind. This mind is the matrix of all matter.

Stephan Schwartz (Science journalist)

I regard consciousness as fundamental. I regard matter as derivative from consciousness.

Max Planck (Developer of quantum theory)

I am inclined to the idealistic theory that consciousness is fundamental, and that the material universe is derivative from consciousness, not consciousness from the material universe. The universe seems to me to be nearer to a great thought than a great machine. It may well be that each individual consciousness ought to be compared to a brain-cell in a universal mind.

Sir James Jeans (British mathematician and astronomer)

It is not only possible but fairly probable, that psyche and matter are two different aspects of one and the same thing.

Carl Jung (Psychiatrist and psychoanalyst)

The universe is not conscious; consciousness is the universe.

Rupert Spira (International teacher of the Advaita Vedanta and an English studio potter)

That consciousness is fundamental is an ancient observation, articulated in most if not all of the ancient religions, East, West and indigenous, spoken of variously as “God,” “The Ground Of All Being,” “Ultimate Reality,” “spirit,” “soul,” “ether,” “akasha” and so on. In the 16th century, the Roman Church affected a separation between the emerging discipline of science and faith. Matter became the domain of science, and consciousness (spirit) was the business of the religion. One of the consequences of this was the separation of the individual self—the body perceived as a container for the soul, the brain a container for mind. Today, high school classes and university departments continue to divide science (objective analysis) and religion (subjective experience). Now, the emerging perception that our bodies, minds and spirits are different vibrations of one Reality—consciousness—has resulted in “integral” studies in science, art and business, and significantly, the blossoming field of “consciousness studies,” where rigorous research is underway.

The fundamental reality is not matter but energy, and the laws of nature are not rules of mechanistic interaction but the ‘instructions’ or ‘algorithms’ coding patterns of energy.

Ervin Laszlo (Hungarian philosopher of science, systems theorist, integral theorist and classical pianist)

Contemplating the above image and how it contains pure potential for every image ever produced—or will be produced—consider the screen you’re looking at right now. What you are seeing is the “collapse” or manifestation of my thoughts, represented in image and words, accessed from the Ground Of All Being. According to my readings, each individuated consciousness, as a derivative, participates in and draws from universal consciousness—that Ground. We experience it as imagination and inspiration, or simply “thought.” And we draw from it according to individual perception, needs and desires. An analogy often used to help us understand The Ground, is a computer or television screen turned off. Relative to the images projected onto them, the screen itself is stable, enduring, unlimited pure potential. It can display—actualize—the totality of visual information that exists in the universe. In this way, from unified nothingness, comes the potential for actualizing everything real or imagined.

Its ground state, the cosmos, is a coherent sea of vibration; pure potential. The waves that emerge in its excited state are the actualization of this potential, and they convey the vibration of the ground state. Consequently the clusters that constitute the manifest entities of the universe are in-formed by the vibration of the cosmic ground state. Object-like patterns and clusters of patterns in the high-frequency band are in-formed by the constraints and degrees of freedom that constitutes the laws of nature; and mind-like patterns in the low-frequency band reflect and resonate with the intelligence that permeates the wave field of the excited state cosmos.

Ervin Laszlo

The reason we all seem to share the same world is not that there is one world ‘out there’ known by innumerable separate minds, but rather that each of our minds is precipitated within, informed by, and a modulation of the same infinite consciousness. There is indeed one world that each of the shares, but that world is not made of matter; it is a vibration of mind, and all there is to mind is infinite, indivisible consciousness.

Rupert Spira

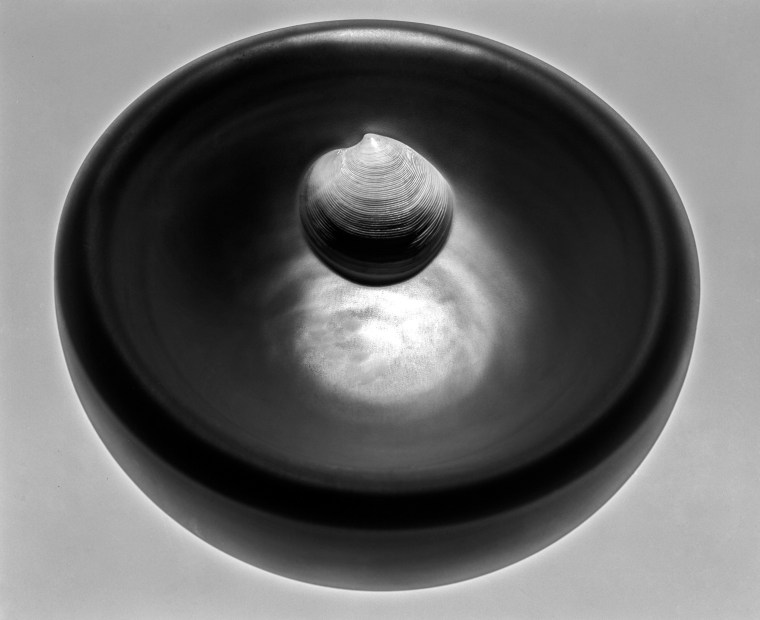

To illustrate the process of actualization, read the following descriptions and fix the image in your mind with your eyes closed. Take your time.

- A blade of grass—make it green, then brown.

- A bowl—make it wooden, then ceramic.

- Put an elephant in the bowl—then a flower.

The words triggered your mind to tune into and download aspects of consciousness from The Ground—akasha, spirit, God—whatever name we want to give it. Instantly. And appreciate: images don’t exist anywhere in the brain. Their component energies—size, shape, softness, hardness, color, etc.—are energy stimulations, vibrations “collapsed” from the Ground, creating a composite “mentation,” a mental image and a representative experience of an object.

Imagine your senses completely turned off. You can’t see, hear, taste, touch or smell. You have no reference for where you are or what is supporting you, because you can’t sense gravity. This is the Ground state, and the only thing that can be said about it is that it is. It exists. Personally, it’s the state of “I am”—a singularity, an individuated Ground actualized from the One, Ground Of All Being. Again, from my readings, evidence comes from the fact that every human being who ever lived and ever will live claims the same name in referring to him or herself—I.

In religious language, the feeling of love is God’s footprint in the heart. It is the experience of our shared being. Likewise, the thought ‘I am’ is God’s signature in my mind. The knowledge ‘I am’ is the shared light of infinite, indivisible consciousness refracted into an apparent multiplicity and diversity of selves or minds.

Rupert Spira

There’s a lot to contemplate here. As individual “grounds” of the Universal Ground—holograms of a sort—might each of us, and humanity as a whole, have unlimited potentials to create? Already we create our personal, professional and collective realities. And what’s the dynamic here? We can only experience the world in duality, in subject-object relationship, so how do we relate to the deep reality of nonduality?

Consciousness has to divide itself—into a subject that knows and an object that is known—in order to manifest creation. It has to sacrifice the unity of its own infinite, and indivisible being and seem to become a separate-self world, which now appears, as a result, to acquire its own independent existence. Thus, the inside self and the outside world are the inevitable duality that constitutes manifestation. They are two sides of the same coin: the apparent veiling of reality.

Rupert Spira

Everything already is. All we have to do is pull it out and make it be.

Linda Smith (My wife and editor)

Okay, given these perspectives, what would be an appropriate response? Science recommends the study and investigation of the material universe. Faith traditions—spirituality—advise prayer and meditation. Seems to me their integration makes sense. Study activates and focuses the mind; prayer and meditation stills it, takes it to Ground.

Below is an image that came into being when I reached out to The Ground and “asked”—through wondering, imagining and playing—how I could combine something nature-made with something man-made.

Resources

Laszlo, Ervin. The Connectivity Hypotheses: Foundations of an Integral Science of Quantum, Cosmos, Life, and Consciousness. 2003.

Whole systems orientation.

Laszlo, Ervin. What Is Reality? The New Map of Cosmos and Consciousness. 2016

Scientific orientation.

Spira, Rupert. The Nature of Consciousness: Essays on the Unity of Mind and Matter. 2017.

Spiritual orientation.

Wilber, Ken. The Eye Of Spirit: An Integral Vision for a World Gone Slightly Mad. 2001.

Integral, human development orientation.