Chapter 13: Line

Harrold, South Dakota

Lines serve to define length, distance and shape, indicating boundaries and separate forms, textures and colors that move the eye and create the illusion of depth—like railroad tracks to the horizon. Physically, they can be many or few, take many shapes, have thickness and depth, length and texture with varying degrees of brightness.

And lines can consist of light and shadow, both specular and diffuse.

In geometry, a “point” is a location. A “line” is an extension of a point, an elongated mark, a connection between two points or the edge of an object or situation. Artist Paul Klee said, “A line is a dot out for a walk.” It can define a space by outlining and creating boundaries between visual elements, be used as a signal, suggest movement and flow within a frame and evoke emotional responses. In photographs that create patterns and geometric shapes, circles and zigzags create a sense of motion; static lines suggest calm or stillness.

Downtown, Columbus, Ohio

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519 CE) initiated a revolution in art by using architectural lines to direct the eye to a vanishing point as in The Last Supper. Artists in the East drew and painted calligraphic lines as part of their spiritual practice. For Chinese artist Wang Xizhi (303-361 CE), brushstrokes were a way to emphasize the harmony of the cosmos. And Andreas Gursky, a contemporary German photographer, became known for his large format architecture and landscape color photographs, made from a high point of view. Apparently, “line” topped the list of his aesthetic preferences.

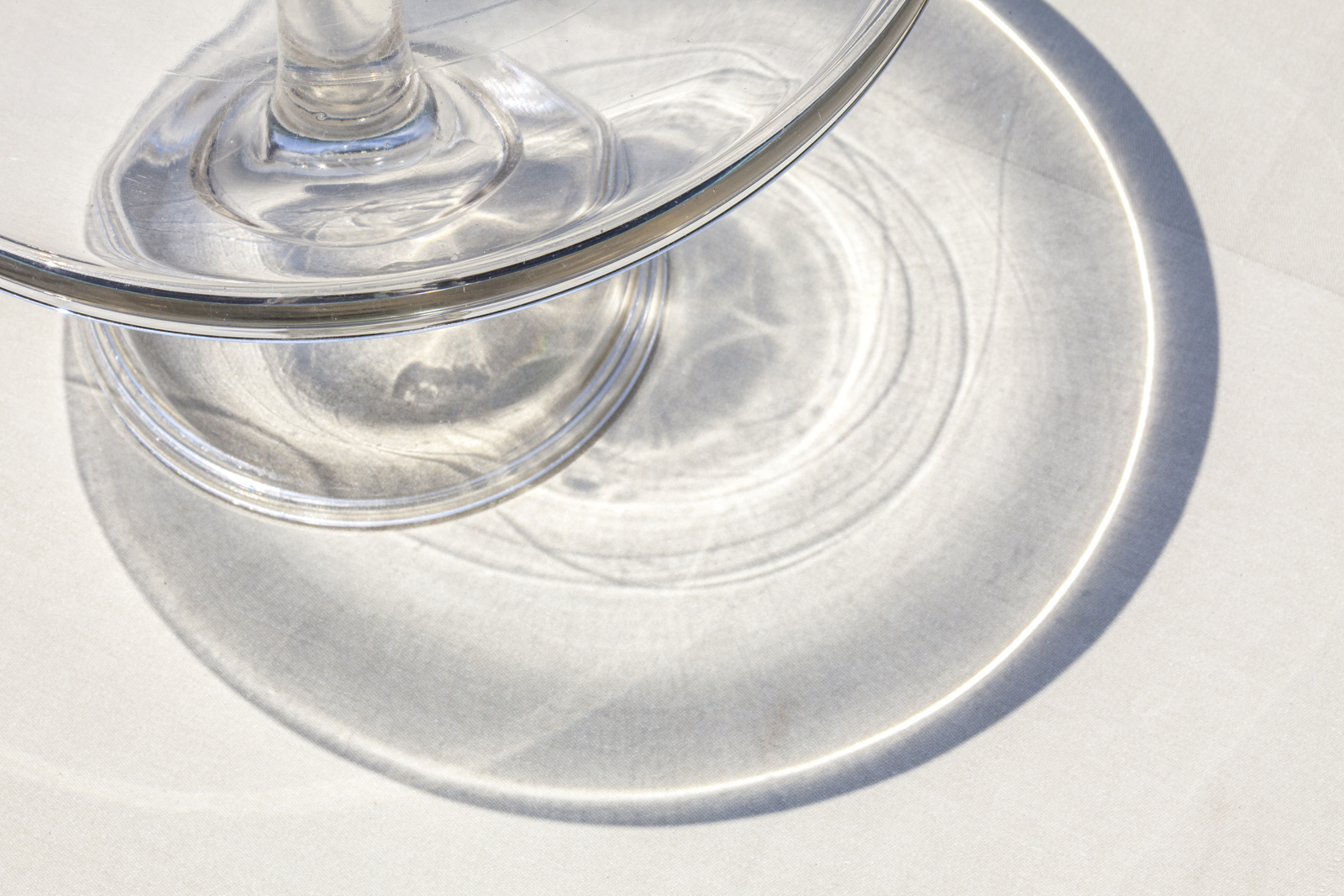

This line of highlighted water serves to separate textures and tones. Lines of light like this can make an image pleasing to the eye, because we’re attracted to highlights, especially when they separate darker tones.

APPLICATION

Horizontal lines have a meditative quality, conveying a sense of calmness, tranquility and expansiveness. They divide an image harmoniously, structuring elements in a way that feels natural and ordered, leading the eye across an image to create a sense of flow. Italian photographer Franco Fontana is best known for his abstract color landscapes, strong in vertical and horizontal lines with discordant color.

Vertical lines suggest growth, solidity and permanence. They tend to be rigid, stable and strong, often seen in architecture, trees, telephone poles and electric towers, windmills, waterfalls and mountain peaks. Lines guiding the eye upward evoke ideas of growth, ambition and transcendence. Slim vertical lines evoke a sense of grace, whereas thick lines convey a more grounded and weighted sensibility.

The eye tends to follow lines, so artists use them as vectors, directing the viewer’s attention to elements of interest. Here, besides the railroad tracks which are lines of light, other lines include the diminishing telephone poles and wires, railroad ties and the horizon itself which leads to the sun.

Research has shown that our perception of elements within a frame happens at 13 milliseconds. This, combined with eons of artistic pictorial expression, has shown that an expressive composition results from the intentional placement of linear elements. Lines are especially emphasized by combining an unusual camera angle with deep depth of field.

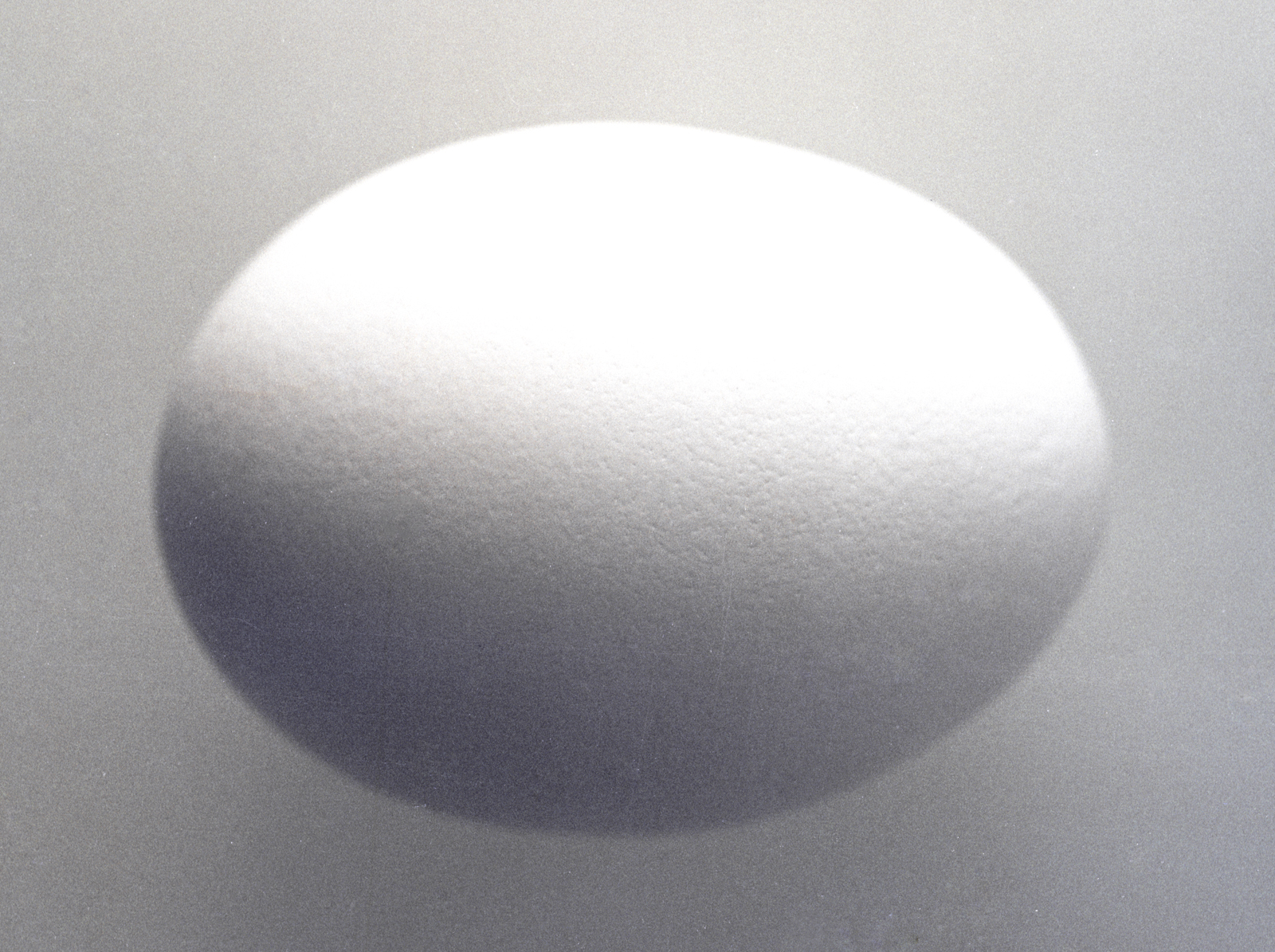

Artists have characterized shadows as “organic lines.” When broken or varying in thickness, texture, shape or color they help to describe edges and create depth. Their position in the composition helps to define the primary subject and its location. And the sharpness or blurriness of shadow edges indicate the specularity or diffuseness of the light source, including its relative brightness. Here, they contribute to the sensibility of a warm, bright summer day.

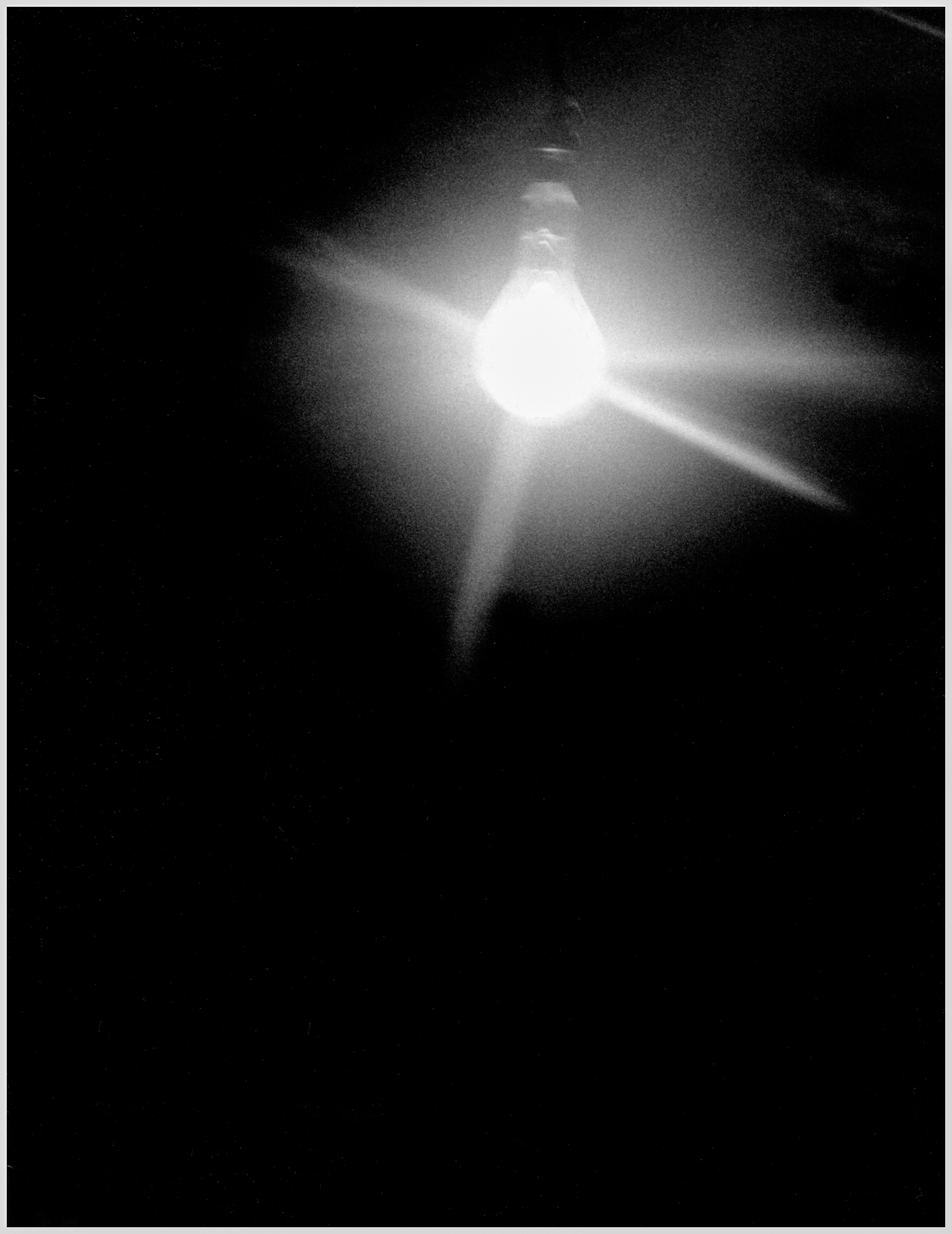

Lines can also be ephemeral, for instance, a ray of light, an airplane vapor trail or a line of fog in a valley. In this instance, sunlight streaking through windows on the dome at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, conveys a sense of divine presence. The dome itself displays a series of concentric circles in the architecture, directing the eye heavenward to a point of light.

TECHNIQUE

Amish hey shocks

Vertical Lines are powerful, leading the eye upward. The closer to the subject, the more likely they are to be bent. A view camera with swings and tilts is often used to get the lines exactly parallel. Images made with a Single Lens Reflex (SLR) camera can also correct for “barrel” and other distortions with editing software. Contemporary French photographer Hélèn Binet often works with vertical lines in architecture. Strong lines, exquisite light and shadow constitute her aesthetic preferences.

As a reminder, the point of this series which demonstrates the variety of aesthetic dimensions is to encourage you to become aware of them in your photographing (or other visual art form), toward identifying the top 3-5 preferences that constitute your unique “style.” Once known, they will guide your choices of location, subject matter and composition making your creative expression truly authentic.

Horizontal lines are restful, calm and serene. They suggest gravity, depth and breadth—converging railroad tracks, rolling hills and meadows, a line of fences, a sprawling farm, a thin stream meandering through tall grass and weeds. Thes lines are enhanced by removing distractions so there’s a clean division between elements and compositions that are clearly about one thing. Look for flowing horizontal patterns in nature—rolling hills, sand dunes or winding roads. Consider long exposures where clouds and water are moving, so they can be blurred. To extend the exposure, us a tripod and neutral density (ND) filters in front of the lens. Michael Kenna’s images will surely inspire you along these “lines.”

New York, close to Lincoln Center

Lines that intersect suggest strength, tension and durability. Their crossing can convey a sense of convergence or conflict. As directional vectors, the eye is drawn to the point of intersection before it explores the other elements in the frame. Because the above lines consist of light, they create depth and express a dynamic flow that’s balanced, equally strong left to right. Intersecting lines can also tell a story, represent collaboration or resolution, even mark moments of change or transition. They can also create a visual metaphor for journeys, relationships or conflict resolution.

Diagonal lines are dynamic. They express the energies of activity, restlessness, drama and opposition—wind-blown trees, a severely tilted barn, an uplifted rock face, contemporary architectural features, an ascending airplane. Lines of light are particularly distinctive, especially against a dark or black background.

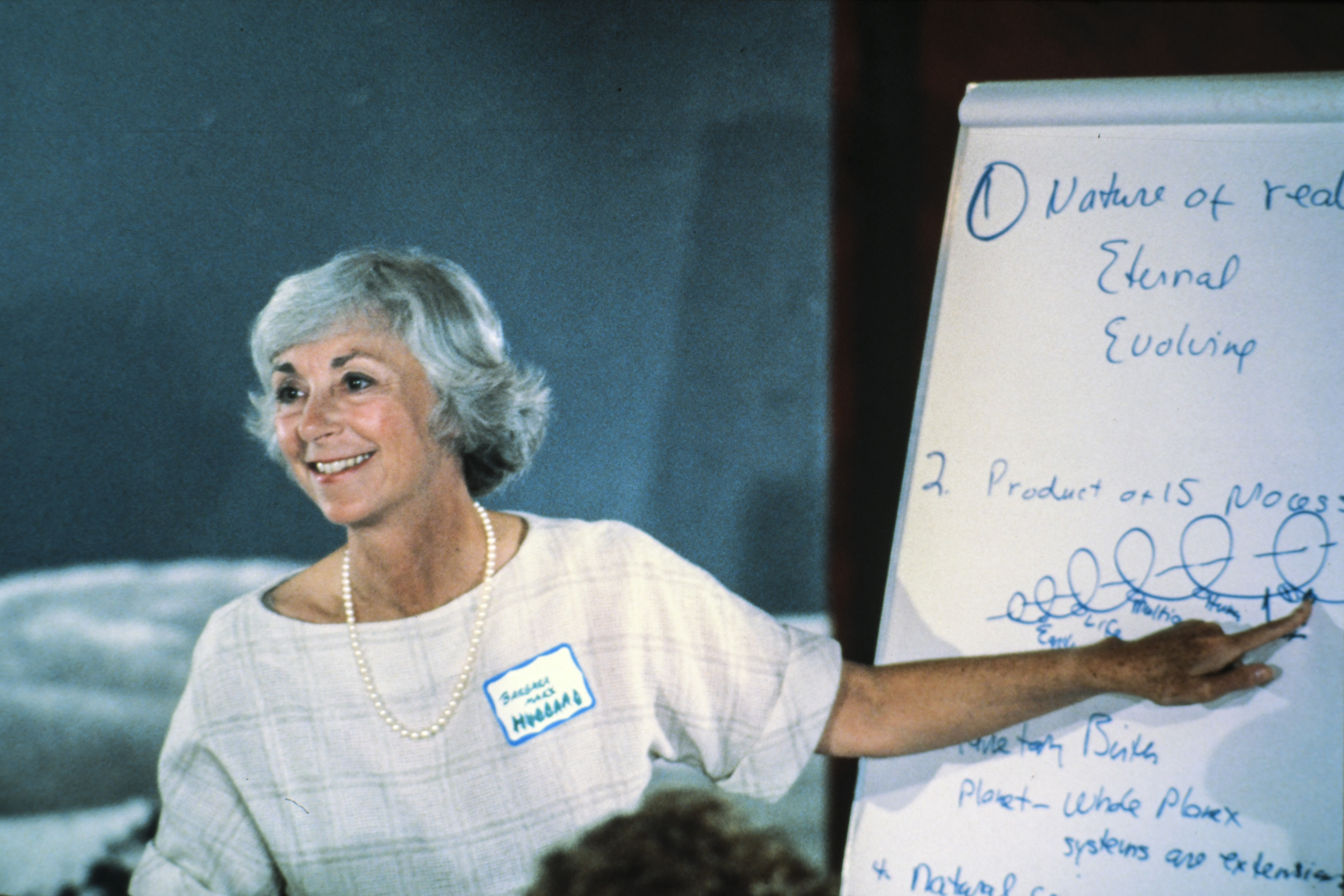

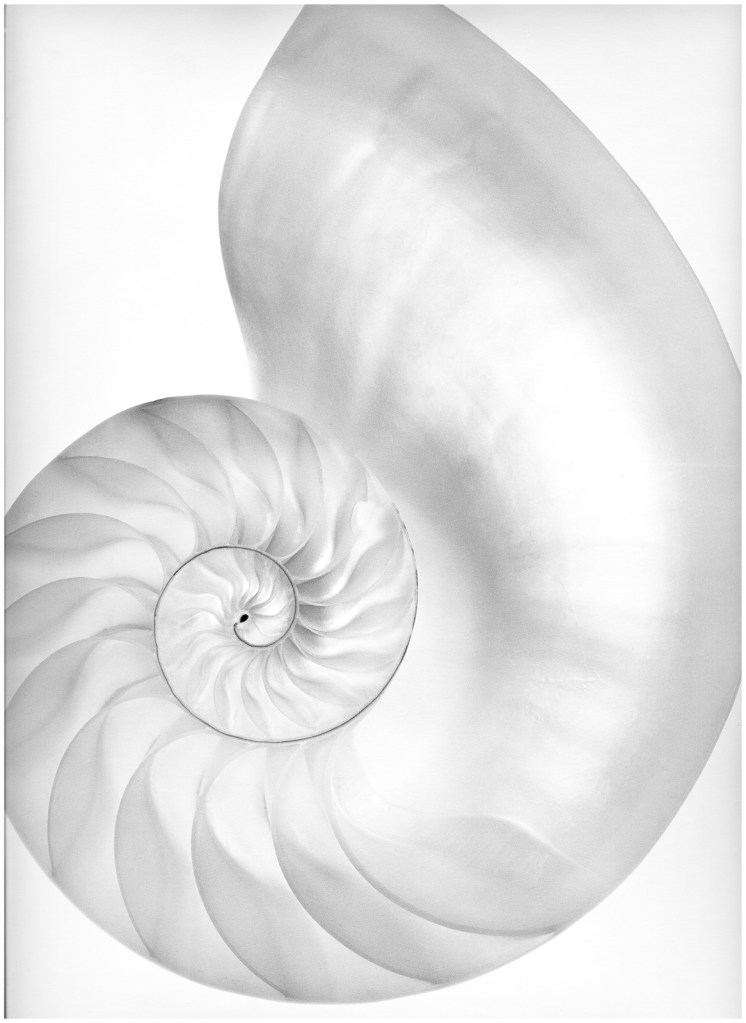

Straight, sharp and bold lines are assertive. Curved, thin, and continuous lines soften. It’s one reason why, aesthetically speaking, straight lines are considered “masculine,” and curving lines “feminine,” particularly in architecture. And finally, lines can be imaginary. Photographers and filmmakers make use of “sight lines,” the direction people in the frame are looking. Generally, we don’t want these lines to lead the viewer out of the frame, preferring to have a person direct their gaze either toward the camera, to another person or an important object or situation.

CONTEMPLATING “LINES” IN PERSONAL AND SOCIAL CONTEXTS

We all draw lines in life. How and where we draw them is an expression of our beliefs and values. Often, these can trigger an emotional response—people standing in line, waiting for hours in the rain or cold, segments of society being excluded, walls to keep immigrants out.

We resolve conflicts by “drawing a line in the sand.” Sitting in a line of traffic for a long period tests the patience of drivers, at times to the brink of road rage. We’re “sold a line of goods” by Robo callers who are directed to follow a “line of thinking.” In the military and certain companies, people are required to “fall in line” behind a leader. In these and other such situations, the choice is social alignment, deciding whether or not to follow someone else’s lead or thinking, conform to a request or behavior. We want to know if it’s “in line” with our beliefs and values.

How and where society draws its lines reveals its collective consciousness. In anthropology and sociology, the phenomenon of drawing lines around groups of human beings is referred to as “stratification.” It’s how we position ourselves relative to the groups we identify with in relationship to outsiders, making distinctions according to kin, tribe, caste, race, geography, economic status and intelligence to name just some of the common groupings.

Landscape photographers in the United States are severely restricted due to every bit of land being owned or enclosed by lines such as buildings, walls and fences. Our environments are filled with fences, telephone poles, electric towers and wires, wind turbines and cell phone towers. It’s why photographers favor state and national parks and travel to other countries and wilderness destinations. In rural England it’s very different. While farmland is owned, its fences have gates for the express purpose of allowing people to walk the property without needing to ask permission. And there’s strict governmental regulation about where poles and towers can be placed. The lines we draw communicate. And what they say has everything to do with how we perceive our neighbors.

Maya women separating and binding stacks of onions.

On a research trip to Guatemala, I followed a Maya guide on walking paths through hills and valleys where vegetables were being grown. One of the notable features was the lack of fences—anywhere. Individual plots were marked by rows of low stone or trees that only grow five feet tall (seen in this photograph). Walking paths through the fields were open to anyone and were often used as shortcuts to various destinations. Where there’s trust, there’s no need to build fences.

The opposite of trust is control; control is an announcement that we do not trust.

Benjamin Shield, craniosacral therapist

____________________________________________________________________

My other sites:

David L. Smith Photography Portfolio.com

Ancient Maya Cultural Traits.com: Weekly blog featuring the traits that made this civilization unique

Spiritual Visionaries.com: A library of 81 free videos on YouTube featuring visionaries and events of the 1980s.