Seeing the Divine as Relationship

While researching for my post “What Makes a True Leader” (October 19, 2025), it became apparent that “dominators” historically created and thrived due to a hierarchical social structure. Thinking about it, I began to realize that hierarchies are pervasive; we take them for granted. In Western religious traditions, the spiritual journey has long been imagined, taught and depicted in art as a vertical ascent, a climb from human to divine, from earth “below” to heaven “above,” with models of holiness and spiritual teaching coming “down” to us through intermediaries such as priests, prophets, mystics, saints and kings.

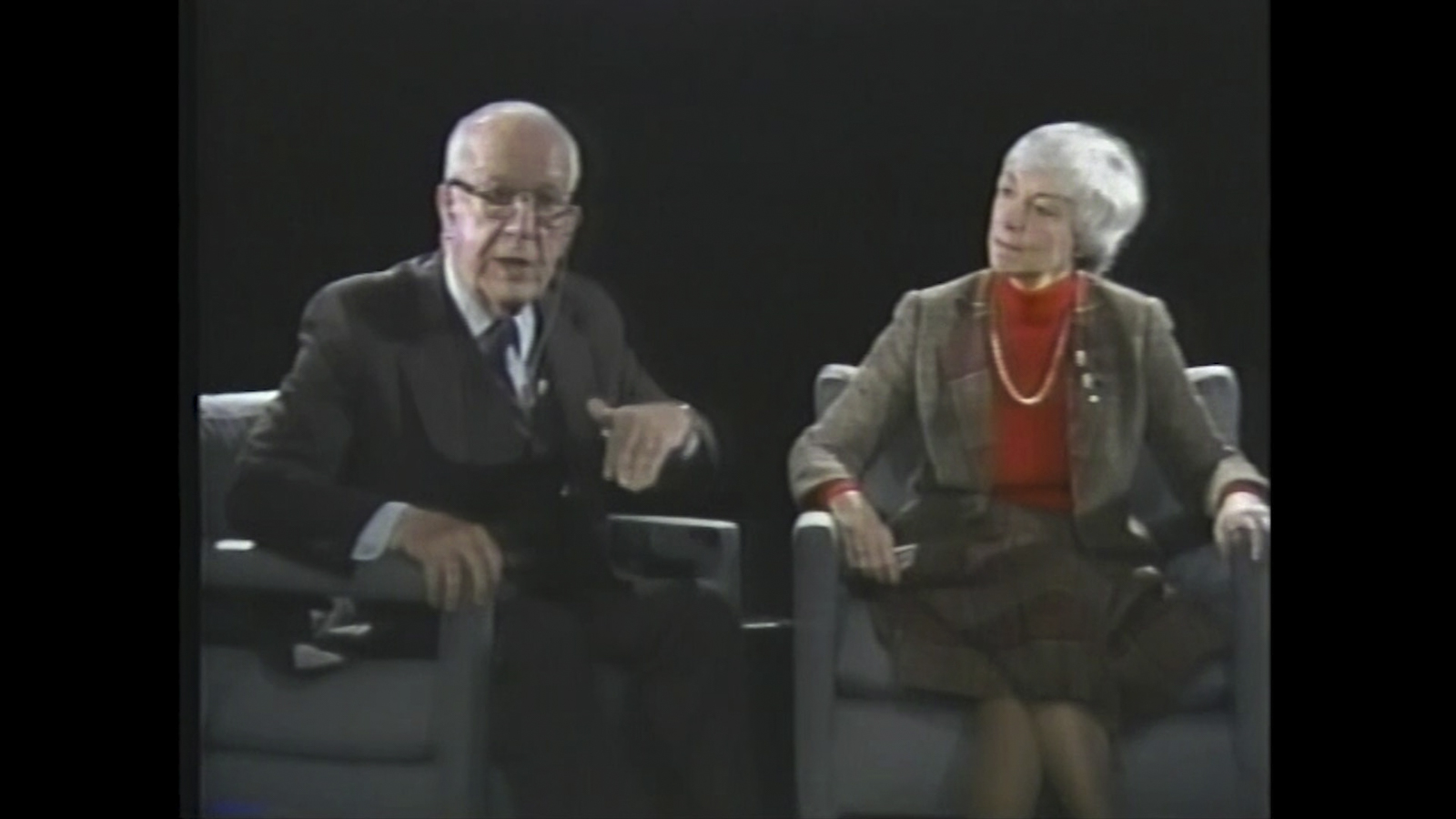

On one of my walks with philosopher Beatrice Bruteau, the conversation turned to the nature of the spirit world. Having read quite a bit on Theosophy, which places “devas,” “logoi,” “masters” and “elementals” on different hierarchical planes of spiritual attainment, I asked about the “ascended masters.” She paused, turned to me and said definitively, “I don’t believe in hierarchy.”

Reality is not a hierarchy to climb, but a communion to join

Beatrice Bruteau, philosopher, author

Duality

Metaphysically, a hierarchical structure of the spiritual domain is considered “dualistic.” It imagines a great chain of being that reflects degrees of holiness rising from mortals to saints, to “heavenly hosts” and then God. It mirrors how the mind perceives everyday reality as composed of ranks where the higher governs or enlightens the lower. The dualistic cosmologies—common in Theosophy, Neoplatonism and medieval Christianity—can inspire awe and order and provide models (saints) who’ve apparently completed the spiritual journey successfully. In dualism, everything flows downward from Source, and the task of the soul is to ascend upward to unite with it.

Nonduality

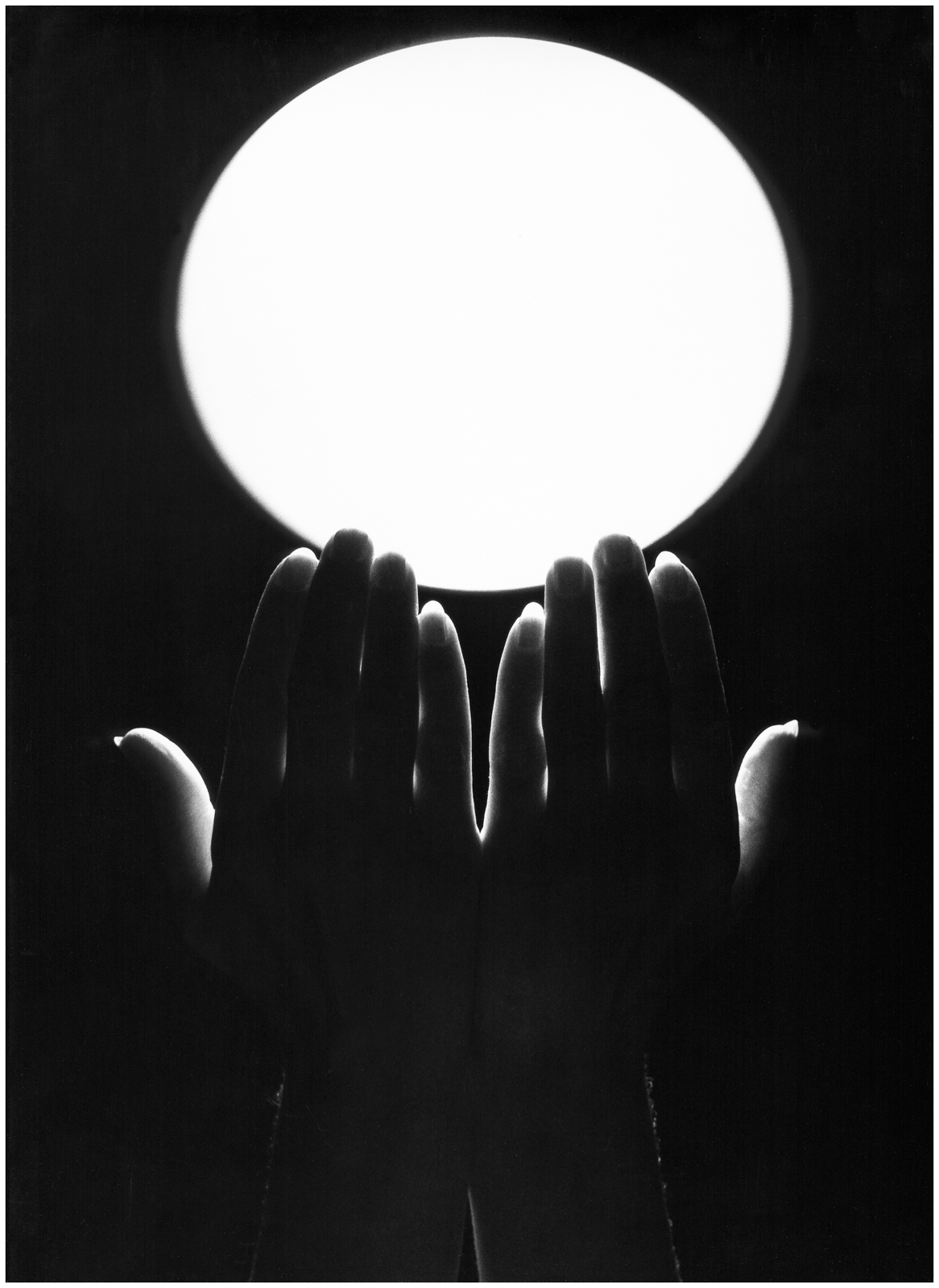

In contrast, the “non-dual” perspective sees all levels of existence as expressions of one undivided reality. Rather than a distance to climb, the spirit world is considered a whole, a unity in which every being, from the humblest creature to the highest intelligence, shares the same divine essence. Hierarchies may still appear as useful descriptions of differing functions or forms, but not as absolute separations of value or nearness to God. From this view, “higher” and “lower” transform into sacred presence and wholeness—the divine shining equally in and through all.

The deepest reality is not substance, but communion.

Beatrice Bruteau, author God’s Ecstasy

When Beatrice spoke about non-dual “communion” as opposed to the dualistic “domination” paradigm, she said there’s no distance between creature and Creator. The example she provides in The Grand Option: Personal Transformation and a New Creation is Jesus washing the feet of his disciples at the Last Supper. Even against their objections, he regarded them as friends in communion (physically and spiritually), equally loved in the eyes of God. None higher or lower.

A Sampling of Nondual Perspectives

Writing in Everything Is God: The Radical Path of Nondual Judaism, Rabbi Jay Michaelson sees divinity not as a distant monarch but as the very substance of existence itself. He writes, “Everyone and everything manifests God… He is not some old man in the sky but is everything we see and everything we are.” From this perspective, God is not a “being,” but being itself, so the soul’s task is not to climb or rise, but to recognize, become aware of one’s true nature.

British social scientist John Heron applied the nondual perspective to the spheres of social and interpersonal relationships. In Participatory Spirituality: A Fairwell to Authoritarian Religion, he talked about “invisible hierarchies of worth between clergy and laity, master and disciple, divine and human.” In contrast and aligned with Beatrice, he believed that “Genuine spirituality is developed in and through persons in relation”—which echoes Jesus’ phrase, “The kingdom of God is within you.” (Luke 17:21). So Heron sees spirituality as a practice to be developed in our relations with other persons, ideally participating in a wider co-creative community “wherever people meet in authenticity and mutual empowerment.”

Jeff Foster is a British spiritual teacher and humorist who talks about the spiritual realm in the language of nonduality with a focus on healing from trauma. In Life Without a Centre: Awakening from the Dream of Separation, he advises, “Simply noticing what is already present, here and now. One could say this noticing is what you are.” In this view, when we awaken to what he calls “effortless presence,” the quest dissolves. “There is no teacher and no taught, no higher or lower—only this infinite intimacy now.”

Meister Eckhart, a 14th Century German Catholic priest and mystic, spoke about the “ground of the soul.” Regarding the spiritual journey he wrote, “there is no rank nor degree.” He reasoned that there couldn’t be a hierarchy because God is not “up there, but in here”—the soul, the radiant center shared by all.

Dorothee Sölle, a German Lutheran and liberation theologian wrote that, “Transcendence is no longer to be understood as being independent of everything and ruling over everything else, but rather as being bound up in the web of life… That means we move from God-above-us to God-within-us and overcome false transcendence hierarchically conceived.”

And Starhawk (born Miriam Simos), an American feminist, writes in Dreaming the Dark: Magic, Sex, and Politics, “A spiritual organization with a hierarchical structure can convey only the consciousness of estrangement, regardless of what teachings or deep inspirations are at its root. The structure itself reinforces the idea that some people are inherently more worthy than others.”

On Balance

Although it’s apparent that my perspective is non-dual, I’m not trying to promote it. I highly respect the dualistic view, was brought up in it and it served me well. It offers hope and provides moral clarity, a clear sense of right and wrong and good and evil, which is helpful for ethical decision-making, and the contrast between the sacred and the profane can inspire spiritual development and inner transformation. The stories of holy people certainly provide insight into dealing with life’s trials and triumphs. And seeing God distinct from creation allows for petitioning prayer, worship and community-building services. The dualistic perspective was beautifully expressed by the Austrian-Israeli philosopher Martin Buber in his popular book I and Thou.

Does It Matter?

The title of my October 12, 2025 post was “How We See Others Matters Greatly.” Here, I’m suggesting that how we see God—Source, Ground of All Being, Cosmic Intelligence or beliefs in general—matter. I will add my opinion, but first I defer to some established nondual thinkers—

We do not see things as they are; we see them as we are.

Jacob Israel Liberman, Rabbi, philosopher

We become what we behold.

William Blake, English poet, philosopher

The kingdom of God is within.

Luke 17:21, evangelist

The eye with which I see God is the eye with which God sees me.

Meister Eckhart, German priest, mystic

Everything participates in the divine life.

Thomas Berry, priest, ecologian

The divine life is not a pyramid of power but a communion of persons.

Beatrice Bruteau, philosopher

Now I think what matters is whatever draws us up, lifts the spirit, brings peace of mind, gives us hope and joy, inspires and empowers us to give our gifts with enough whole systems health to make a difference for the world and those whose lives we touch. The cultivation of self-love, expressing love and being mindful that we are love is enough.

__________________________________________________

My other sites:

David L. Smith Photography Portfolio.com

Ancient Maya Cultural Traits.com: Weekly blog featuring the traits that made this civilization unique.

Spiritual Visionaries.com: Access to 81 free videos on YouTube featuring thought leaders and events of the 1980s.