A time to ponder and assess

As December 21st approaches, I reflect on the significance that the winter solstice held for indigenous people and mark it in my own life as a way to attune, as they did, to the order and rhythms of nature and the cosmos. Having studied Mesoamerican cultures, particularly the ancient Maya, for many decades, I use them as my general reference here. But all indigenous cultures the world around, from Egypt to Indonesia, had rituals based on the summer and winter solstices.

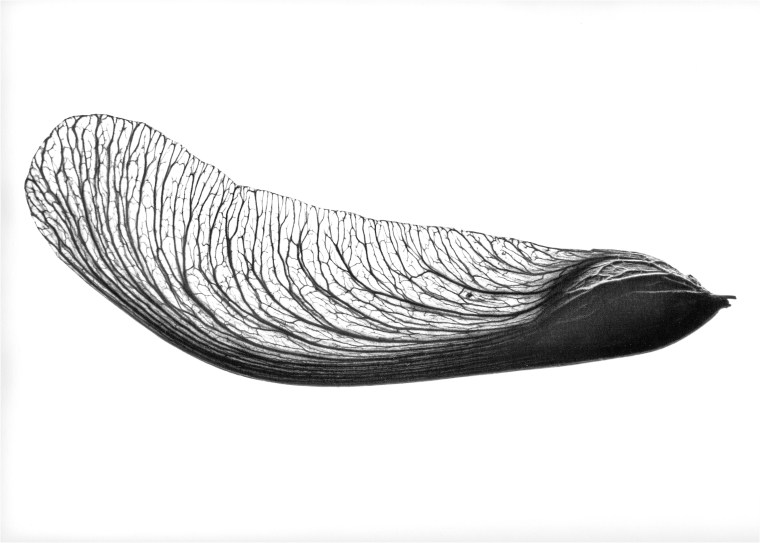

Without instrumentation, the ancients developed their understanding of the world by observing the movements of the sun, moon, planets and other celestial bodies. The sun was viewed as the creator because it was known to be the source and sustainer of all life—an observation that is, of course, accurate, whatever name we attach to our star.

For the Maya, Ajaw K’in, “Lord Sun” and his movements were therefore of primary concern. His risings and descendings made the day, and his journeys made the seasons. They didn’t assume the world would continue year after year. Had the sun not risen on the solstice or any other day—perhaps from not being properly fed with prayer, incense and blood (considered the sacred sap of life; without it, there is death) the world would end. Every day, the sun’s ascension from the underworld was considered a rebirth. His dying, indicated by his descent at dusk, was seen as the necessary precursor for his rising or rebirth. The cyclical pattern of rising and falling and “traveling” along the horizon established the model for everything that lives.

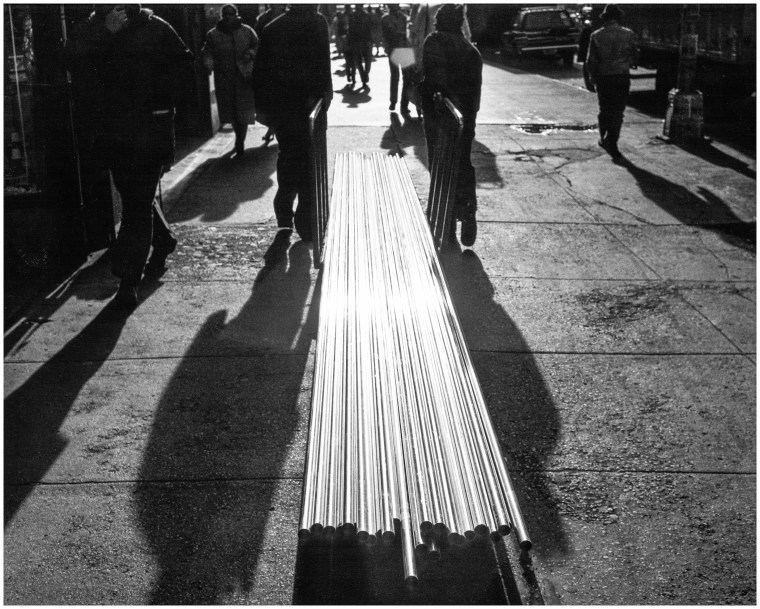

Every morning, for hundreds of years, generations of sun priests got up well before dawn and stood on the steps of a temple facing due east to observe and mark the position of the sun. Initially, they sighted the sun rising atop tall posts they set on the horizon, and later the poles were replaced with temple rooftops.

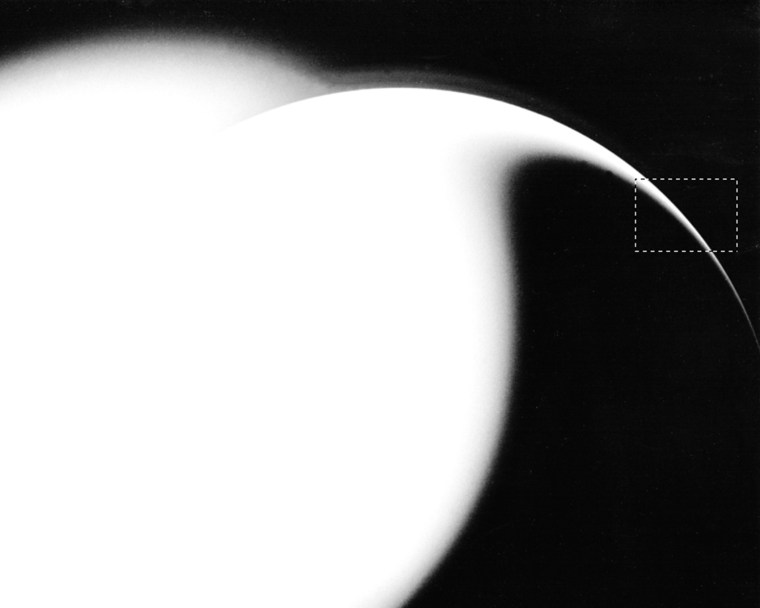

From June to December they noted how the sun moved beyond the temple in a southerly direction. Then, on the morning of December 21st (in our calendar) something astonishing happened. (The exact date can vary by a day depending on the location and year). The sun “rested.” It stood still. And that was a cause for concern. Was Ajaw K’in trying to decide to make another round of days? Or not? The next day, when the sun rose again over the temple it was cause for great celebration, feasting and ritual dancing. And in the days following, the sky-watchers observed the sun moving north along the horizon. Continuing their observation, on the summer solstice, June 21st, the sun paused again and began his journey south again.

The significance of this “turnabout” for the ancients was that it indicated a time of rest and a change of direction. As above, so below—in life and the way they lived. It was a time for renewal, new beginnings, and rebirth. Logically, since the sun and the other celestial bodies (all perceived as gods) were so orderly in their journeys, the way to honor them and encourage their continuance was not only to offer prayers and sacrifices in rituals, but also to emulate them, bringing peace and order into the household and the community. One of the reasons why I was attracted to the Maya was that they, more than any other culture, to a remarkable extent, modeled every aspect of their lives on the order, patterns and processes they observed in the sky and in nature. And they sustained that perspective and rituals over a vast territory for millennia.

For me, the winter solstice serves as a reminder to appreciate and align with the order of the universe. It’s a time to pause, take a breath and reassess life’s journey. Is what I’m doing in alignment with my purpose (Why I’m here?) and mission, what I’ve come to do. What are my gifts? Am/How am I giving them to family and those in my circle? What am I contributing to the world? What can I eliminate in order to better focus on what truly matters? Are my priorities consistent with my authentic values? What are the patterns, positive and negative, that persist? Might this be the time to prepare for or take a new direction?

The first peace, which is the most important, is that which comes within the souls of people when they realize their relationship, their oneness with the universe and all its powers, and when they realize that at the center of the universe dwells the Great Spirit and that this center is really everywhere, it is within each of us.

Black Elk, Medicine man of the Oglala Lakota, South Dakota