Evidence of cosmic order

All evolution is a dance of wholes that separate themselves into parts and parts that join into mutually consistent new wholes. We can see it as a repeating, sequentially spiraling pattern: unity to individuation to competition to conflict to negotiation to resolution to cooperation to new levels of unity and so on.

Elisabet Sahtouris, evolution biologist, futurist, author

In 1979 I was interviewing noted scholars, authors, scientists and artists for a television documentary I wanted to produce on the life and philosophy of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. The film never got made but in the course of the research I came to understand that, although the evolutionary process is not predetermined, it is pre-patterned, driven by features that are constant and consistent. Among them are the conservation of energy, increased order and complexity, innovation and reciprocity. In the 80s when chaos theory emerged and mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot displayed his fractal images, these and other patterns became visible, demonstrating that beneath the apparent chaos, in all of nature there is order. From quarks to the cosmos, it’s revealed to us as patterns.

Computers create relationships based on patterns, and clocks display them in segments of time. Patterns of thought bring order and consistency to everyday living, for instance in our routines. Artists in every field look for and incorporate patterns in their works, in large part, consciously or not, because they evidence and reflect the order—some would say the “intelligence”—of the universe.

At a certain point, probably by noticing that I had already photographed lots of patterns, I decided to seek them out. Reading in physics helped me to appreciate that all patterns, whether found in nature or in man-made objects, were evidence of the order intrinsic to the cosmos. This especially became clear in the 90s when scientists learned that matter itself turned out to be patterned arrangements of energy.

And then I gained some perspective on the order within the atom. For instance, if Yankee Stadium were an atom, the nucleus would be smaller than a baseball sitting in center field, and the outer part of the atom (electrons) would be tiny gnats buzzing about in orbits and altitudes where commercial airplanes fly. In between the baseball and the gnats there appears to be nothing, but various technologies reveal them be patterned energy fields.

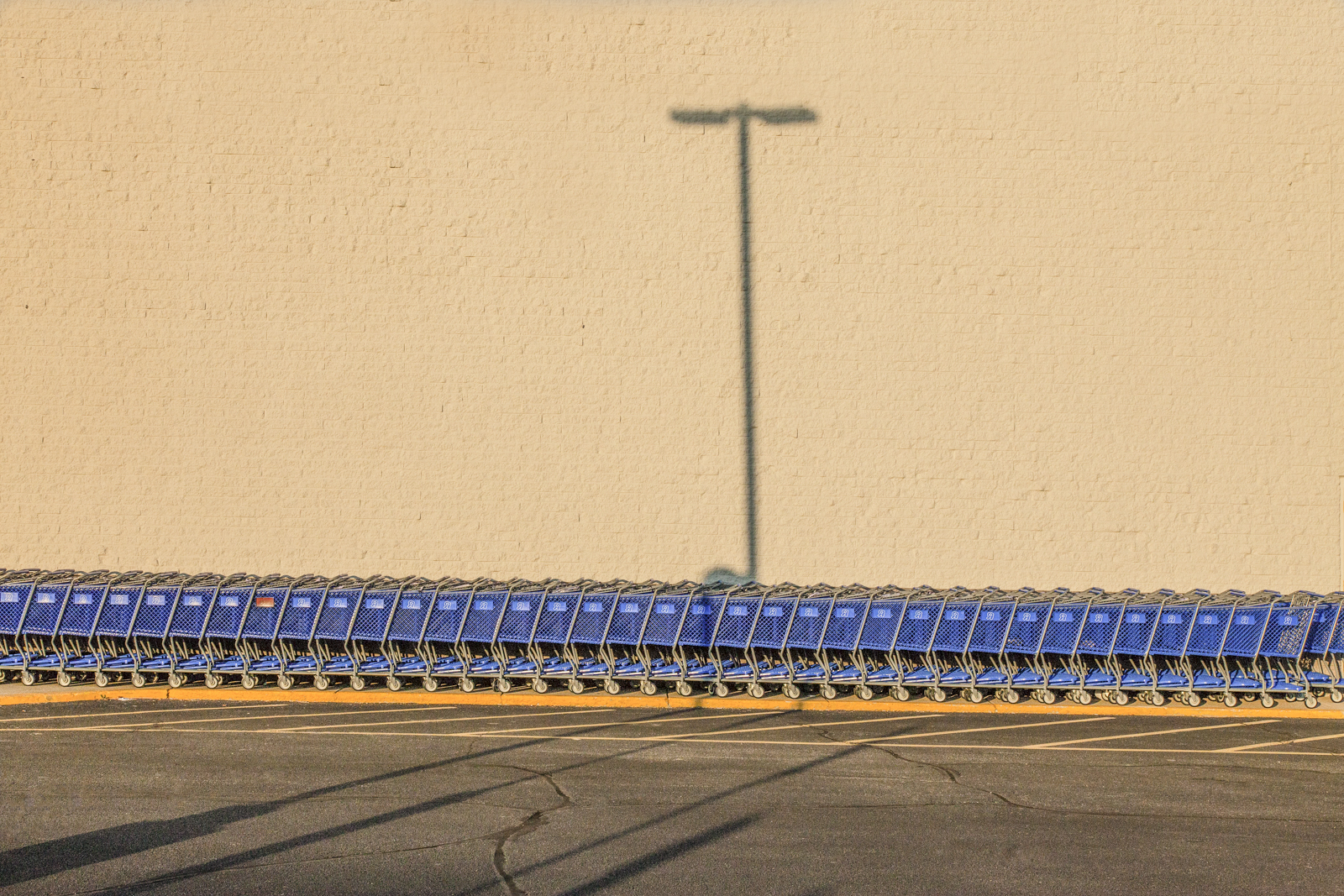

Human-made patterns are evidence of our ability to repeat behaviors and create objects and images that are consistent, even identical, and organize them into coherence. They’re strongly associated with culture, for instance, in building materials, branded shopping carts, clothing and fabric made of Scottish plaid, architecture as seen in Islamic geometry, and in values.

In Patterns of Culture, anthropologist Ruth Benedict observed that “A culture, like an individual, is a more or less consistent pattern of thought and action.” Each culture, she said, chooses from “the great arc of human potentialities” a set of characteristics that become its leading personality traits, and constitutes an “interdependent constellation of aesthetics and values” that make up its unique world view. Here, a conception of the ancient Maya world view and Chak, the rain god, are reflected in the motifs on this building.

Nature-made patterns reveal the underlying order of universal forces including gravity, magnetism, planetary and geologic movement, seasons, climate, wind and wave motion and electric force to name a few.

In some patterns, the order is regular, for instance in snowflakes, spider webs, and fish scales.

In others, such as a tiger’s stripes, tree bark, and soil erosion, the pattern is irregular.

Contemplating Pattern in Personal and Social Contexts

Pattern recognition is critically important in making decisions and judgments, acquiring knowledge, advancing the sciences and expressing creativity. Writing in Psychology Today, psychologists Michele and Robert Root-Berstein write that “The drive to recognize and form patterns can be a spur to curiosity, discovery, and experimentation throughout life.” They cite M.C. Escher and Leonardo da Vinci as artists who purposefully looked for patterns in wood grain, stone walls, stains and clouds—to use in their works and to stimulate thinking beyond convention. They note that every living thing that repeats a form, behavior or process has found a way to survive.

Psychologist, Jamie Hale adds a caution noting that “the tendency to see patterns in everything can lead to seeing things that don’t exist.” His examples of pattern recognition gone awry include “hearing messages when playing records backward, seeing faces on Mars, seeing the Virgin Mary on a piece of toast, superstitious beliefs of all types, and conspiracy theories.” I’d add to this, the turning of a blind eye to the increasing patterns of climate change.

Once in a while it’s good to look at our most repetitious behavioral patterns, the things we do almost every day and ask if they’re producing positive results for ourselves, others, society and the planet. To get a different result, the challenge is to adopt a different pattern—habit. For instance, when ordering iced tea in a restaurant I ask for a paper rather than a plastic cup.

On the social side, Tony Zampella, a sociologist, and leadership coach provides examples of exploitation in several area citing them as destructive social and environmental patterns.

In Labor—exploiting child labor, overworking employees without benefits or overtime, underpaying women in the workforce and hyman trafficking.

In Production—flouting regulations or cutting corners to maximize shareholder value or profits, (think Ford Pinto, the GM switch recalls, the recent Wells Fargo scandal).

In Public policy— exploiting fears to benefit an industry or voting block (think the congressional ban on gun violence research, willful ignorance of tobacco’s link to cancer and denial of climate change).

In Resources— ravaging the planet for political or monetary gain (consider the current fracking debacle, or the Exxon Valdez, or the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill).

As the behavior patterns of these and other cultural, commercial and political systems break down, they’re affecting change in the way we think about ourselves in relation to the Earth. As a consequence, we’re increasingly needing to rethink the workability and philosophy of materialism—the notion that the world is made up of dead atoms, that human consciousness emerged as a development of complex brains, that the resources of the planet are ours to subdue, that securing property, goods, wealth and varieties of experience are the road to happiness and that the purpose of religion is to gain a reward in an afterlife or beneficial rebirth. This—the “domination paradigm”— has been and continues to have dramatic and catastrophic consequences for the environment, the quality of life for humans and animals, and the ecosystems that sustain all life.

Atmospheric scientist, Michael Mann, writing about the jet stream as The Weather Amplifier (Scientific American March 2019), said, “The safest and most cost-effective path forward is to immediately curtail fossil fuel burning and other human activities that elevate greenhouse gas concentrations.” According to philosopher and social scientist Beatrice Bruteau, our best hope lies in the emerging paradigm, what she refers to as the “communion paradigm,” the perception that the earth does not belong to us, that we belong to it, and that all things and people are interconnected in the web of life.

In The Universe Story: From the Primordial Flaring Forth to the Ecozoic Era–A Celebration of the Unfolding of the Cosmos, eco-theologian Thomas Berry and cosmologist Brian Swimme show how the old sectarian story about how the world came to be and where we fit in, is not only dysfunctional but toxic to living systems. Importantly, Dr. Berry distinguishes the “environmental” movement from the “ecological” movement, the former attempting to be a respectful adjustment of the earth to the needs of human beings, whereas the latter is an adjustment of human beings to the needs of the planet. It’s why I’m always looking for leaders whose concern is “ecosystems” rather than “the environment.” According to these authors, the basic tenants of ecosystems are differentiation, which is the foundation of resilience (creating and celebrating variety in all things including people), subjectivity (preserving the inner aspects of life, the “vast mythic, visionary and symbolic world with all its numinous qualities”), and communion (the co-creative, mutually beneficial interrelatedness “that enables life to emerge into being.”) They observe that these three elements are fundamental patterns in the evolution of living systems.

Of course, a change in perception is not enough. It must be matched with commensurate action by individuals and governments, religions, educational institutions and corporations—as filmmaker Michael Mann urges, getting off fossil fuels. Thomas Berry is even more adamant: “All human institutions, professions, programs, and activities must now be judged by the extent to which they inhibit, ignore or foster a human and Earth relationship.”

So what can we do as individuals? We can develop a pattern, a regular practice—habits of recycling, minimizing our carbon and consumption footprints, supporting local and national initiatives in safeguarding or restoring ecosystems, educate ourselves, speak about ecology with family and friends—in person and through social media, and affect even broader influence by consistently voting for leaders who are knowledgeable about ecology and committed to making appropriate responses to climate change a top priority. It deserves that status because the survival and vitality of everything else, without exception, depends on humanity getting into patterns of right relationship with each other and the planet.

The human might better think of itself as a mode of being of the Earth rather than simply as a separate being on the Earth.

Thomas Berry, priest, “ecologian”

For further reading on what we can do, I recommend Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We’re in without Going Crazy by Joanna Macy and Chris Johnstone.

(For pattern photographs in black and white, visit my monograph: Patterns: Evidence of Cosmic Order. Click on the book, enlarge and turn the pages).

_____________________________________________

My other sites:

David L. Smith Photography Portfolio.com

Ancient Maya Cultural Traits.com: Weekly blog featuring the traits that made this civilization unique

Spiritual Visionaries.com: Access to 81 free videos on YouTube featuring thought leaders and events of the 1980s.