Attending to light fosters deep perception and appreciation

I was nineteen and majoring in photography at Rochester Institute of Technology when I made a commitment to the regular practice of black & white photography as a medium of personal growth. Prompted by insights gained from some images I’d made, I sat alone in my car overlooking Lake Ontario and became overwhelmed with tears of joy. I said to myself: Whatever else happens in my life, I will always photograph and learn from the results. Unwittingly, I had adopted an admonition that I encountered years later in the writings of scientist and philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin S.J. “The more one looks,” he said, “the more one sees. And the more one sees, the better one knows where to look.” Many years later I am still on that path, exercising a growing capacity to experience beauty, discover essences and ultimates within commonplace forms and circumstances, and express feelings of appreciation and joy that come as a result.

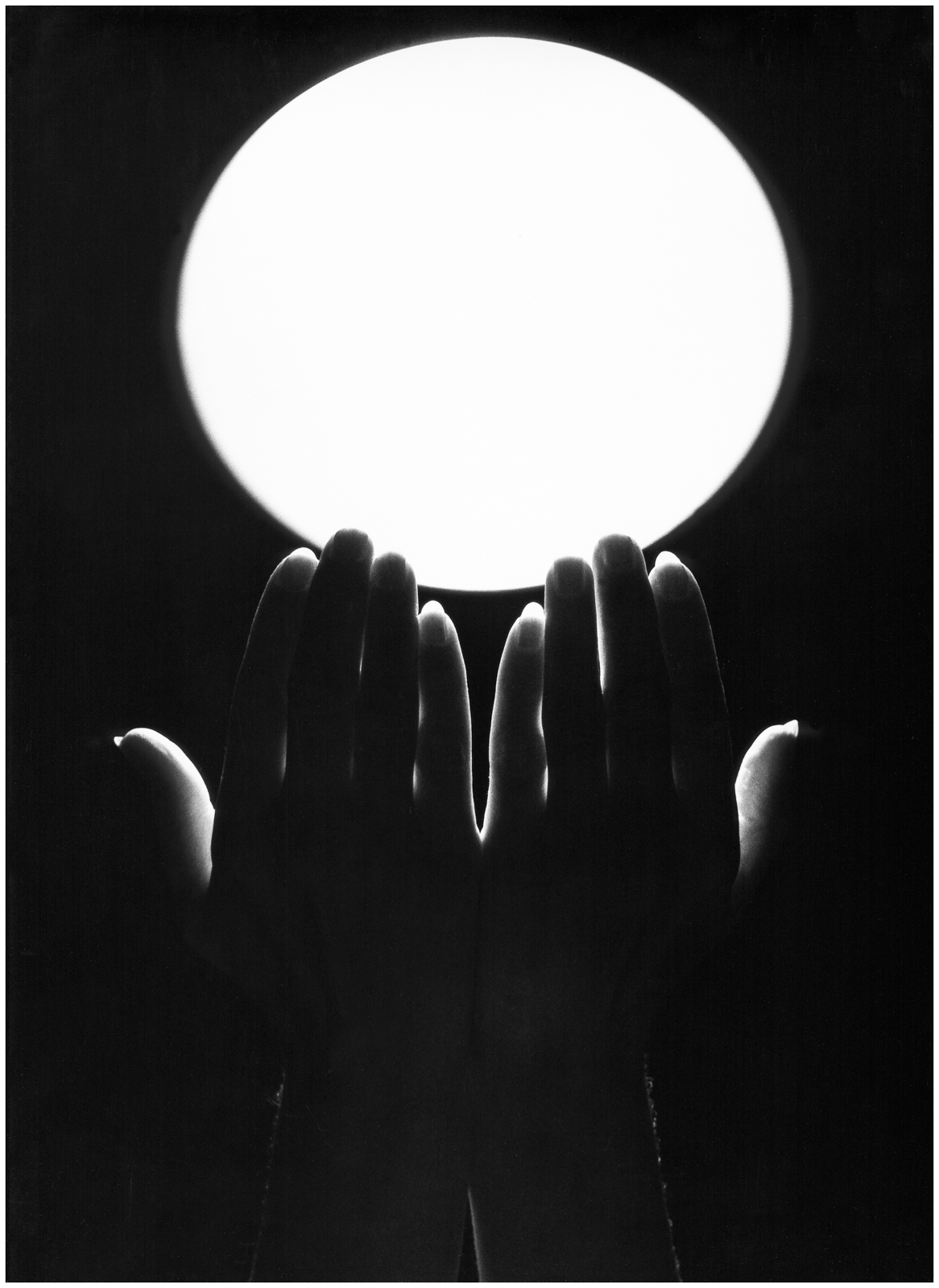

Within a few years of making that commitment I realized that subject matter was taking a back seat to light. Beyond its direction, intensity and color, I hungered for circumstances and a quality of “illumination” that would evoke a sense of the subject’s essential being in relation to All Being—including its process of becoming. I’d experienced this in the works of Ansel Adams, Paul Caponigro, Ruth Bernhard, Edward Steichen and Minor White, so I knew the light without could reveal something of the light within.

But what was that “light within?” And where could I find it? Two experiences suggested a direction. The first was reading Teilhard’s description of love as an energy, “the affinity of being for being.” The other was when I heard Buckminster Fuller say that love is “evolutionary gravity,” the thing that holds everything in the universe together. Signs of affinity are readily available in nature, particularly in objects that display the fundamental order and patterns observed by scientists and mathematicians.

It’s readily available in nature.

It’s readily available in nature.

But could it also be observed in people?

In the built environment?

In commonplace objects we make and use?

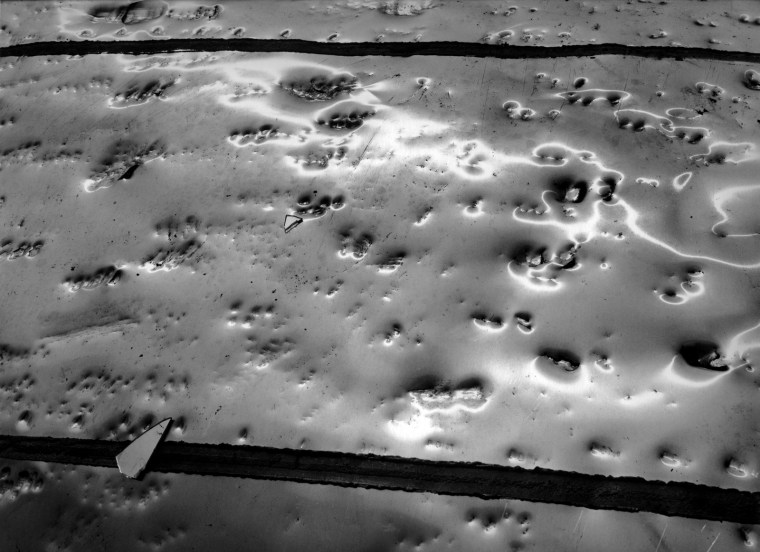

Perhaps seen in a new light or from a different vantage point?

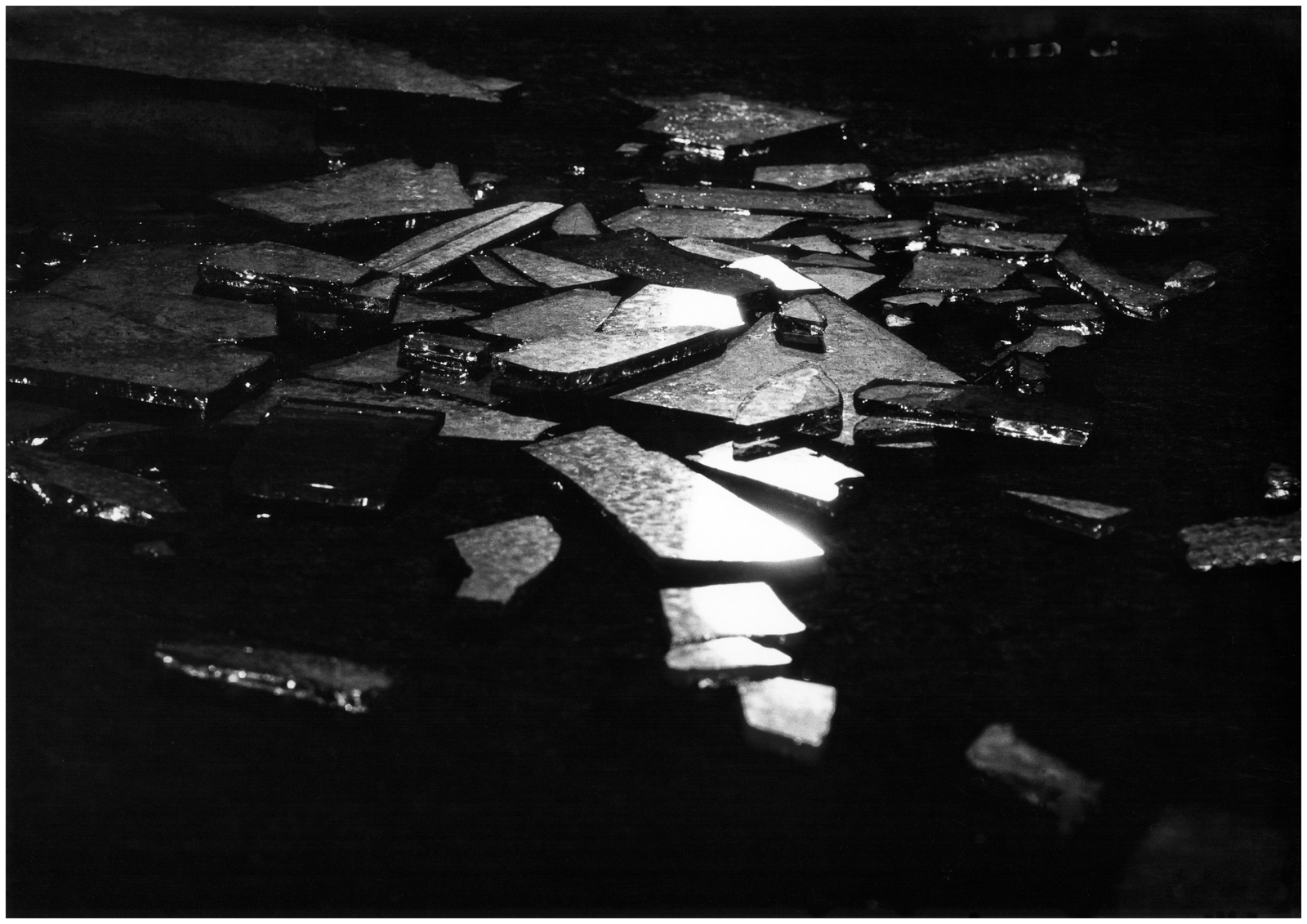

What about objects that no longer serve a purpose? Indeed, the more I looked, the more I saw. And the more I saw, the better I understood where to look. Fast-forwarding through many more years of photographing and scrutinizing the results, I learned that deep perception—-seeing beneath the surface and with understanding eyes— requires both knowledge and imagination.

In 1978 I toured a mushroom farm and came away with a photograph of a dirty old wrench lying on an oil drum. While moving the print from one tray to another, I began thinking about what had to happen in order for that wrench to exist in front of my camera. What was its history? I thought about the farmer who used it last and set it down. I wondered what it was used for and how many other people had used it.

In my mind’s eye I back-timed to see the wrench shiny and new hanging on a pegboard in a hardware store, available for purchase. That led to imagining the steps in its making: the forging process, the molten liquid being poured into a mold, and before that the minerals being mined while a great distance away in time someone sat at a drawing board drafting its form and dimensions. Prior to that, well down the evolutionary spiral, another someone was the first person to visualize the wrench-and-nut as a solution to a problem. And in order for the vision to materialize there had to be an accumulation of knowledge about the properties of metals, especially how to shape and strengthen them. Further down the spiral, I contemplated the frustrations and challenges, the failed experiments and happy accidents that resulted in that knowledge. And what did that require? All the people, time and learning that came before it, including the millions of years of human evolution that led up to it. And what did that require? Billions of years of planetary, solar, galactic and cosmic evolution. And what did that require? The Big Bang. And what did that require?

Up and down the evolutionary spiral: affinity and joining, love and union. “Fuller being is closer union,” Teilhard said. By joining in ways that promote viability and growth, simple forms brought about new, more complex and conscious forms. Primordial forces and sub-atomic particles merged to form atoms. Atoms joined to become molecules. Molecules joined to become cells. Cells joined to become organisms. Organisms joined to become creatures. Human beings joined to become societies. And societies joined to become nations.

That image of the wrench, isolated and illuminated to accentuate its form, texture and context was a statement of being that precipitated my journey down the evolutionary spiral—all the way to Source. At some point, particularly when the light is exquisitely illuminating a person, object or situation, backtiming to the Ground of All Being became natural.

If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.

Carl Sagan, astronomer, author

For more such images, visit my book: Reverence for Light: A contemplative approach to photography. Click on the book, expand the screen and turn the pages.

________________________________________

My other sites:

David L. Smith Photography Portfolio.com

Ancient Maya Cultural Traits.com: Weekly blog featuring the traits that made this civilization unique

Spiritual Visionaries.com: Access to 81 free videos on YouTube featuring thought leaders and events of the 1980s