Chapter 6: Wabi Sabi — The Japanese Aesthetic of Impermanence

We tend to think of entropy as something “bad,” the inevitable tendency of matter to disintegrate, for all living things to die. As embodied creatures, we naturally would prefer to avoid this downward spiral—for ourselves, loved ones, pets, creations, cherished objects and the systems we’ve developed in order to function. Because death is so mysterious, it’s not surprising that it has been and continues to be primary subject matter for storytellers across all time, cultures and media.

The Japanese people, artists in particular, have another way of looking at entropy. For them, “wabi sabi” is both a worldview and an aesthetic perspective based on the acceptance and appreciation of impermanence and imperfection. I so much respect the shift in consciousness that this requires. When entropy is viewed as impermanence, a natural and cosmic principle, disintegration and aging processes can expand our perspective and perceptions, resulting in some beautiful, even important works of art. It’s all about what we choose to see in the world.

In Wabi Sabi For Artists, Designers, Poets And Philosophers, American artist Leonard Koren points out that the Japanese hesitate to explain wabi sabi, but most will claim to understand how it feels. According to Wikipedia, “wabi connotes rustic simplicity, freshness or quietness and can be applied to both natural and human-made objects, or understated elegance… It refers to the creation of beauty through the inclusion of imperfection, focusing on subject matter that is asymmetrical, austere, simple, quiet and modest. Also, it appreciates the randomness of nature and natural processes…” And “sabi is beauty or serenity that comes with age, when the life of the object and its impermanence are evidenced in its patina and wear, or in any visible repairs.”

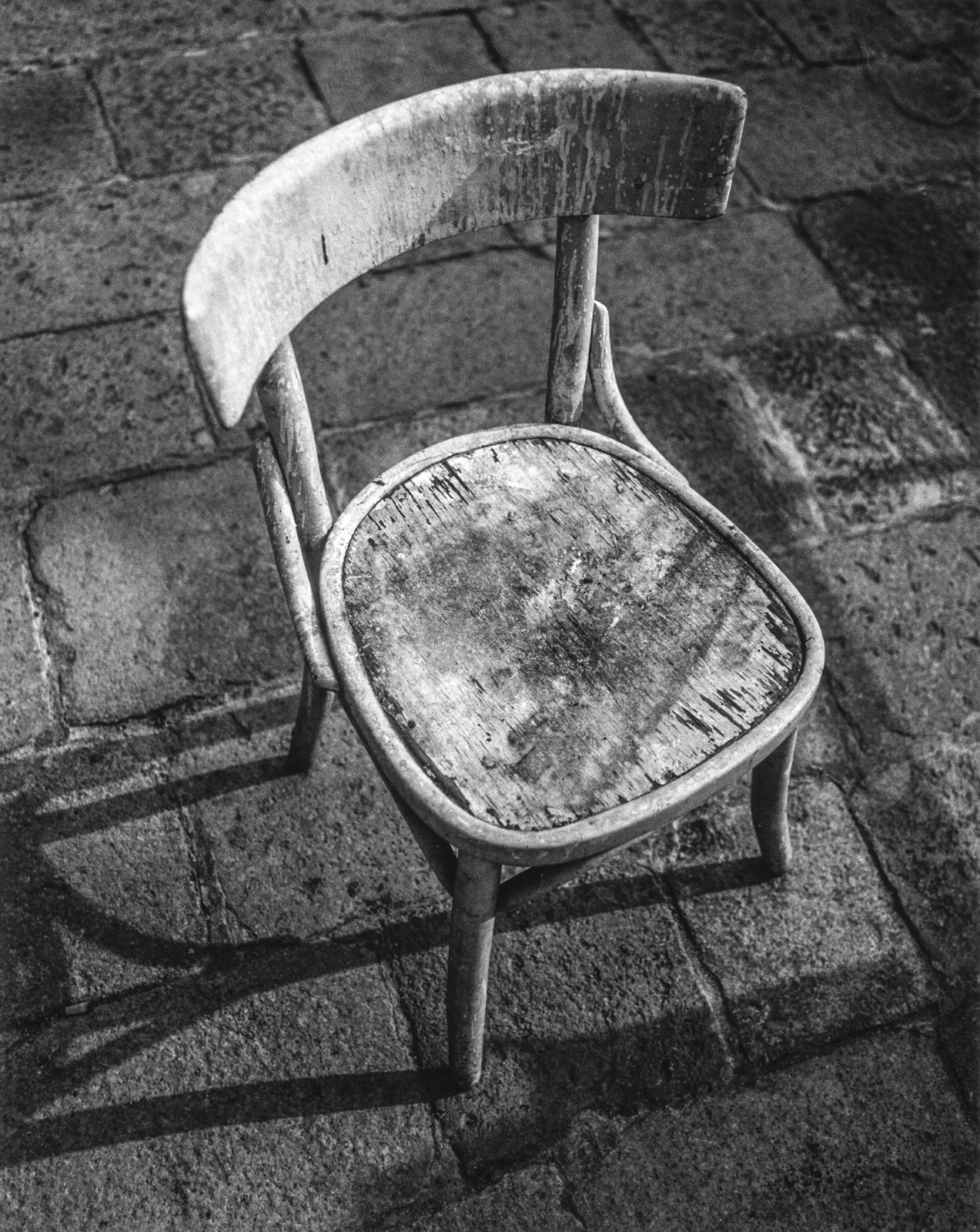

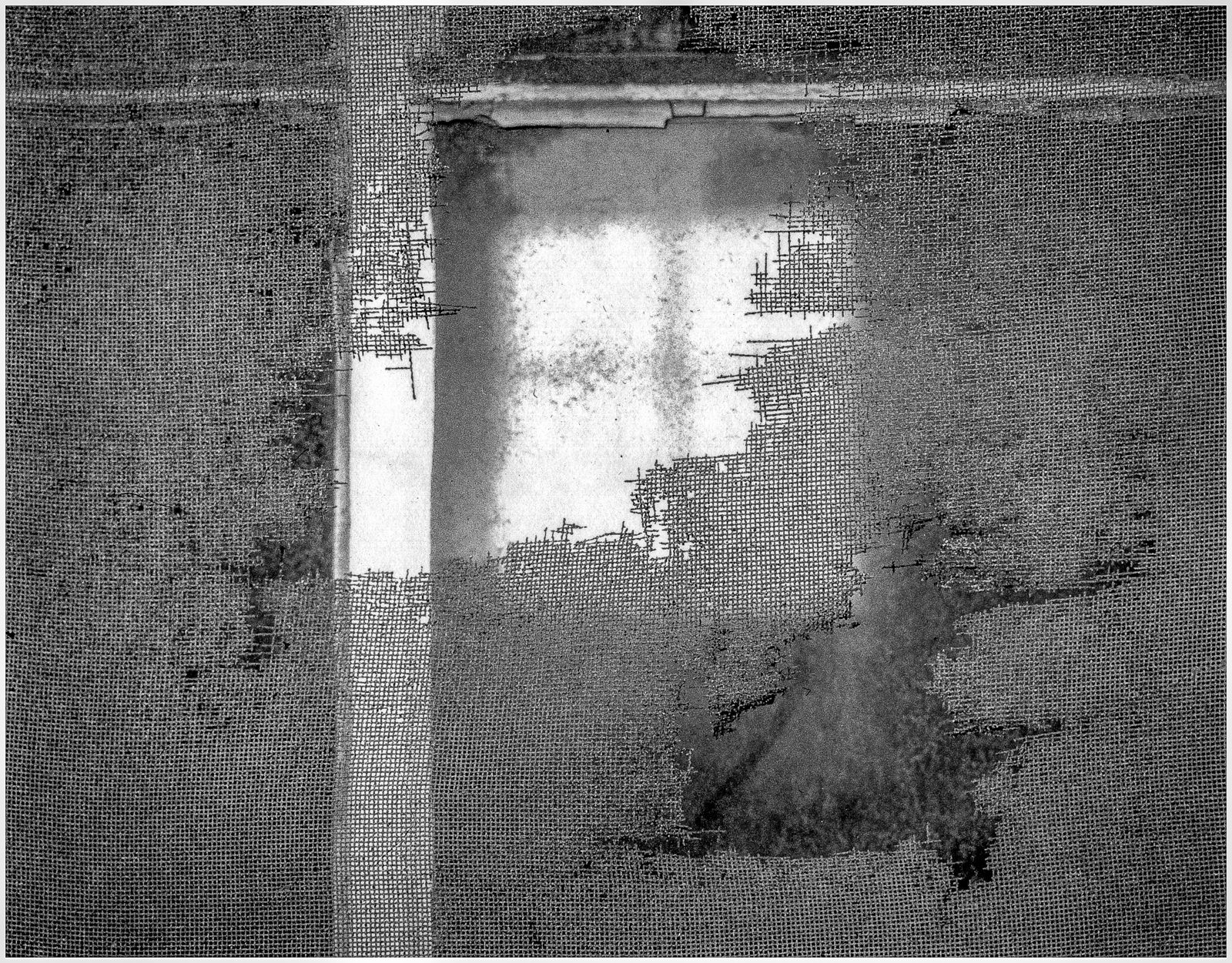

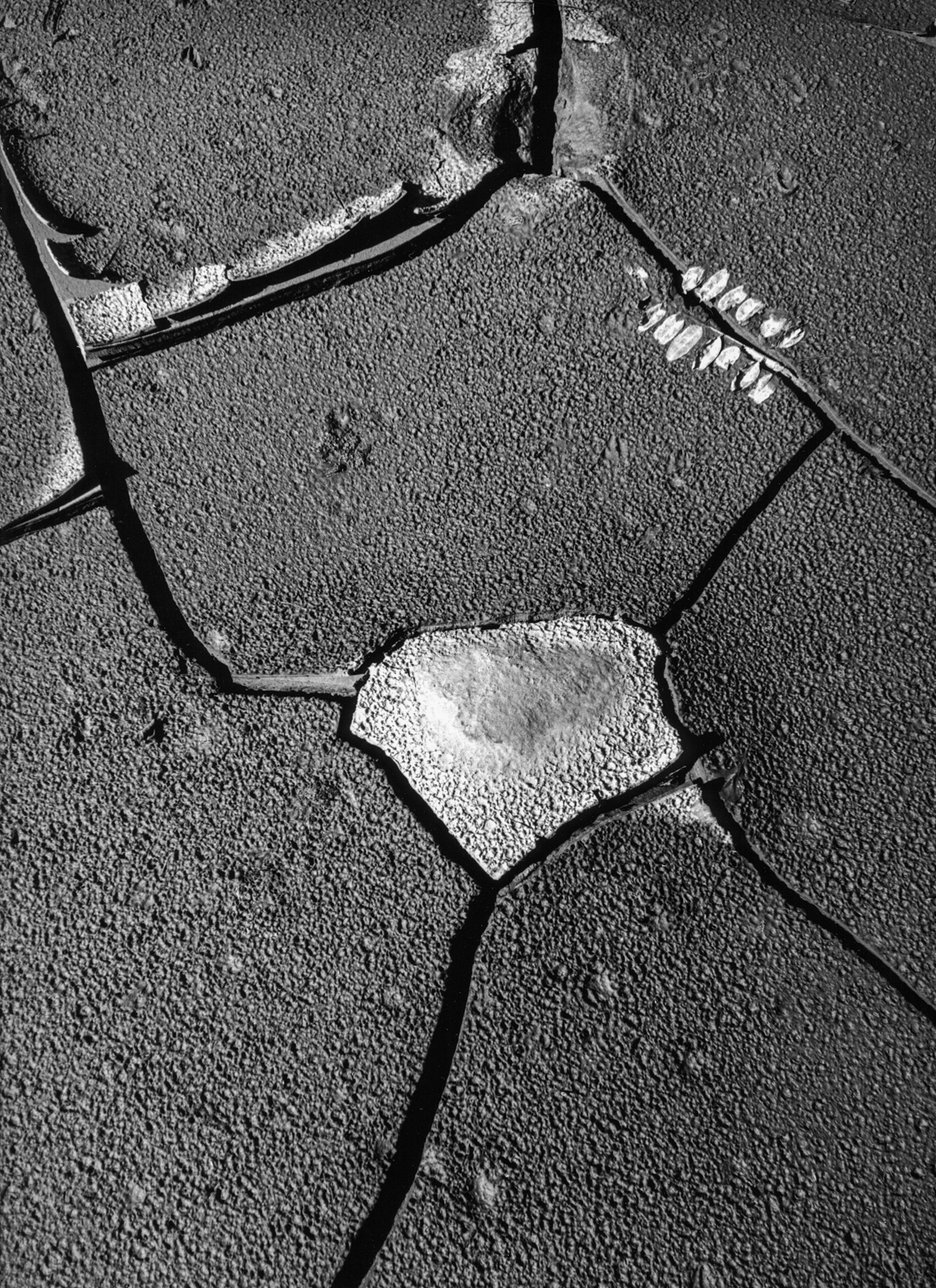

Wabi Sabi regards the signs of dissipation or decay as beautiful—peeling paint, a wilting flower, rusting or pitted metal. According to Mr. Koren, it’s “the most conspicuous and characteristic feature of traditional Japanese beauty.”

Author Andrew Juniper, owner of the Wabi Sabi Design Company in the UK, observes that “If an object of expression can bring about, within us, a sense of serene melancholy and a spiritual longing, then that object could be said to be wabi sabi. It’s for this reason that the bowls used in Japanese tea ceremonies are rustic, simple, sometimes pitted and not quite symmetrical.”

It’s also why fine art and contemplative photographers are drawn to areas where entropy is well underway, including junk yards, abandoned structures, neglected neighborhoods and construction sites. When composed and lit well, textures born of age and weathering can be beautiful and interesting, at times dramatic.

Always, these kinds of environments present an opportunity to practice composition and explore one’s aesthetic. Images made in such places can evoke the sensibilities of aging, abuse and neglect. And for some, they can encourage contemplation. What does this image say to you? By adopting a wabi sabi mindset, the artist can become more attuned to a subject’s characteristic energies—asymmetry, simplicity, quietness or imperfection, how the elements in a composition feel rather than look. In simplicity especially, we appreciate the essence or spirit of things.

Wabi sabi is neither smooth nor complex. It’s the bark of a tree and broken branches, cracks in a vase or concrete wall, creases in a tablecloth, peeling paint or the random spill of oil on a blacktop surface. It’s not the smooth skin or perky expression of the young. Rather, it’s the character lines and calm demeanor that come with age.

Young and aspiring photographers get the impression they have to travel in order to find appealing subject matter. If the intent is to produce “calendar art” that may be so. But for those more interested in exploring and exercising their unique personal aesthetic, I recommend the practice of wabi sabi. It’s also good to work at or or close to home, because it presents more of a challenge to see with fresh eyes and activate the inner eye of understanding a subject’s essence and history beyond surface appearances. For instance, what does an expressive wabi sabi image evoke or reveal? What does it say about the object’s owner or user? Where did it come from? What’s its history? How was it made; what materials?

As perception expands and awareness deepens, we better appreciate that entropy is a natural and cosmic process. Images of impermanence present the artist with a world of opportunities to explore his or her perceptual capabilities and connect to this awesome and beautiful force.

Our souls are all made of the same paper; our uniqueness, though, comes from the creases in that paper from the folding and unfolding of our experiences.

Jiddu Krishnamurti, Indian philosopher, speaker and writer

Rendering subjects in black and white is particularly conducive to wabi sabi, because the emotional appeal of color doesn’t overpower the characteristics of form, texture and simplicity in the aging process. One of the challenges for the visual artist then, is to see all things and all people as beautiful.

Pare down to the essence, but don’t remove the poetry.

Leonard Koren, American artist, aesthetics expert and writer

Recommended Practice

WABI SABI

Create a series of photographs based on the theme, “Entropy Can Be Beautiful.”